When Cynthia Baron invited me to write a book for the Palgrave Studies in Screen Industries and Performance series, I knew this would have to be about Bette Davis and the way in which she developed an effective screen acting method at Warner Bros. in the 1930s. Yet when I began to work on this, I soon realised that there was a much bigger story to be told – story about the way in which one of the largest Hollywood studies had become dedicated to producing prestige pictures based on Broadway plays in the early 1920s, almost ten years before Warners hired Davis as a contract player.

Bette Davis was just one of a long line of actors that Warner Bros. recruited from the New York stage, including John Barrymore in 1924 and Mr George Arliss is 1928. Once I began to see that Bette Davis’ transformation into one of Hollywood’s most successful and acclaimed star actors was part of this bigger project, I decided to tell that story. And in telling it, I hoped to produce a very different impression of Warner Bros. in the 1920s and 1930s from the one that is usually conveyed in the standard history books. This particular Hollywood studio is typically described as a producer of cheap genre films based on newspaper headlines and a specialist in gangster movies, prison pictures and backstage musicals far removed from the smart and sophisticated films being produced at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Paramount at the same time.

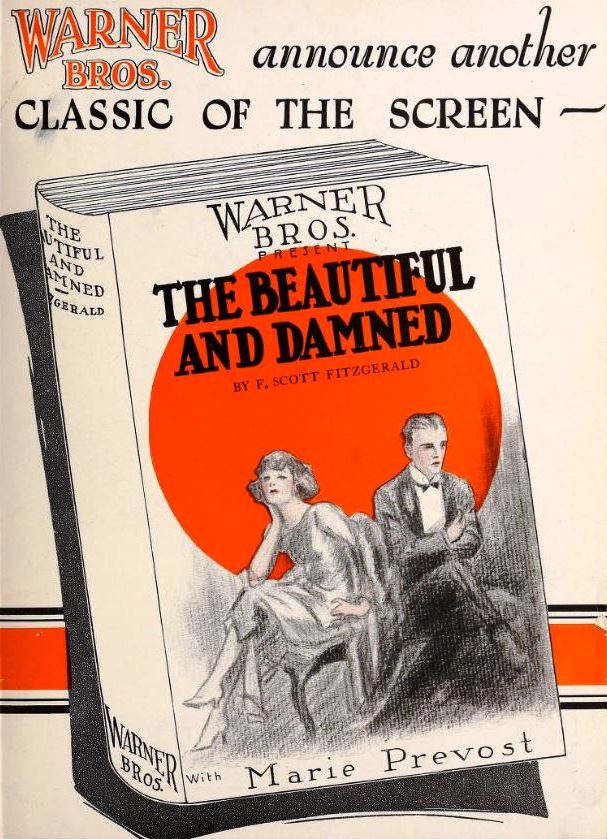

My research quickly confirmed that Warner Bros. was a major producer of biopics, historical costume dramas and romances – many of which were adapted from novels and stage plays – and that the company hired the best of broadway talent in order to produce lavish and costly ‘photoplays,’ many of which were presented under the heading of ‘Classics of the Screen.’

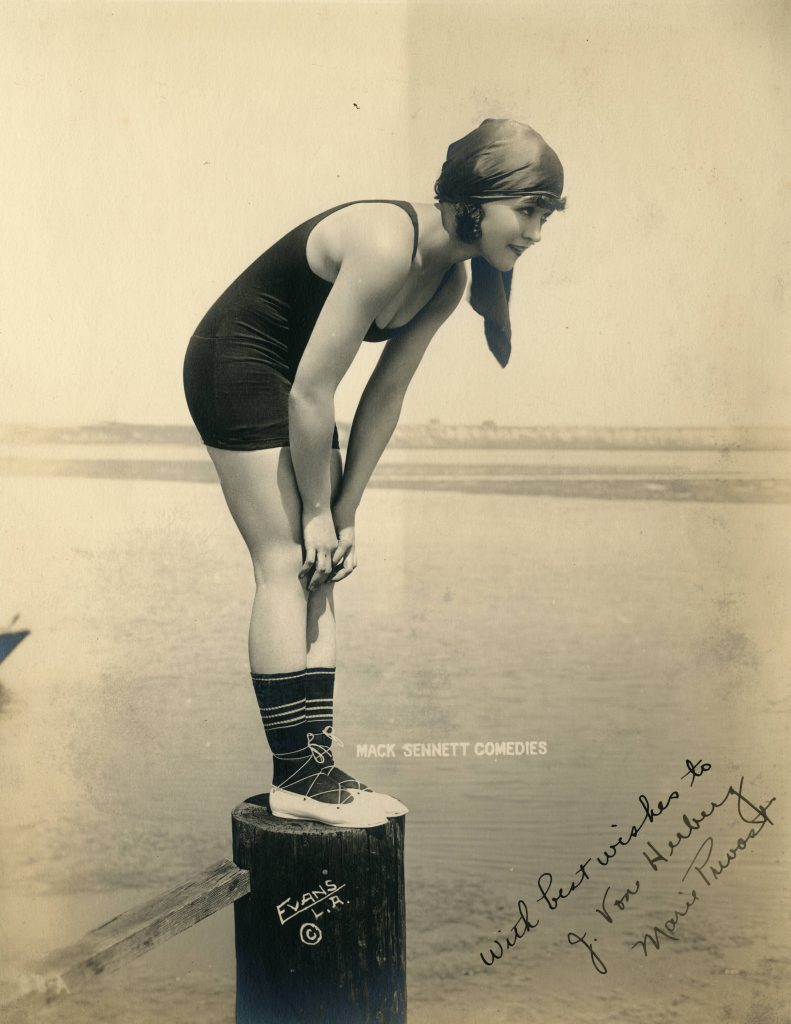

What resulted was a book that explored the wider links between Broadway and Hollywood, between acting for the stage and the screen, one that charted the movement of some of America’s top theatre stars from the New York stage to silent movies and then on to ‘Talking Pictures’ in the mid to late Twenties. Working on this project, not only transformed my understanding of Warner Bros. during the 1920s and 1930s but also the nature of film acting, the multiple and deep links between the theatre and the cinema in the United States and the pioneering work of some rather neglected actors, not only John Barrymore and George Arliss but also Marie Prevost, Monte Blue, Louise Fazenda, Ruth Chatterton, George Brent, Frank McHugh and Leslie Howard.

Blurb on the back cover

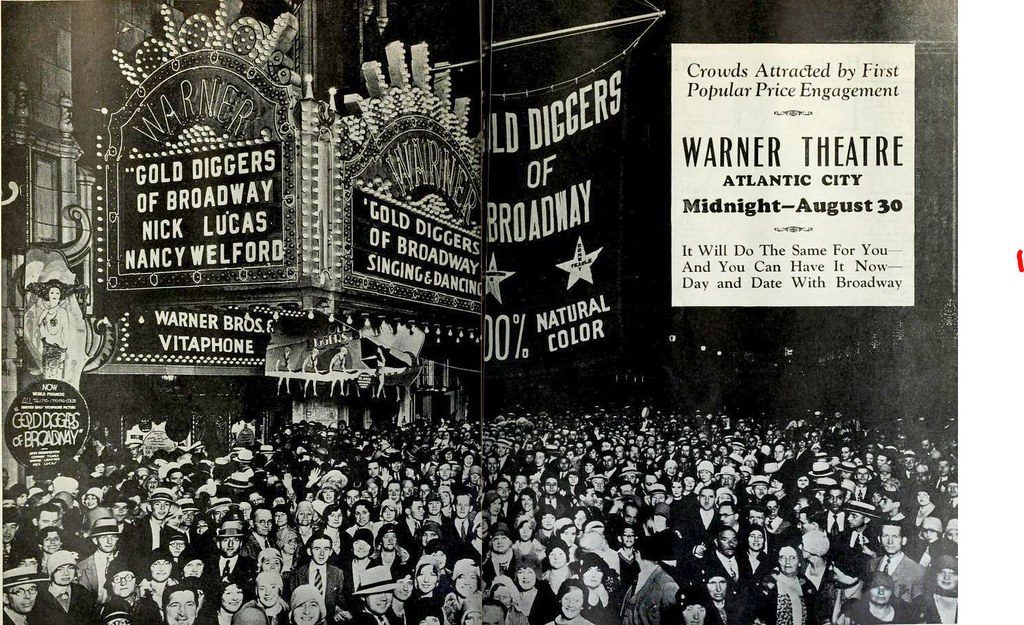

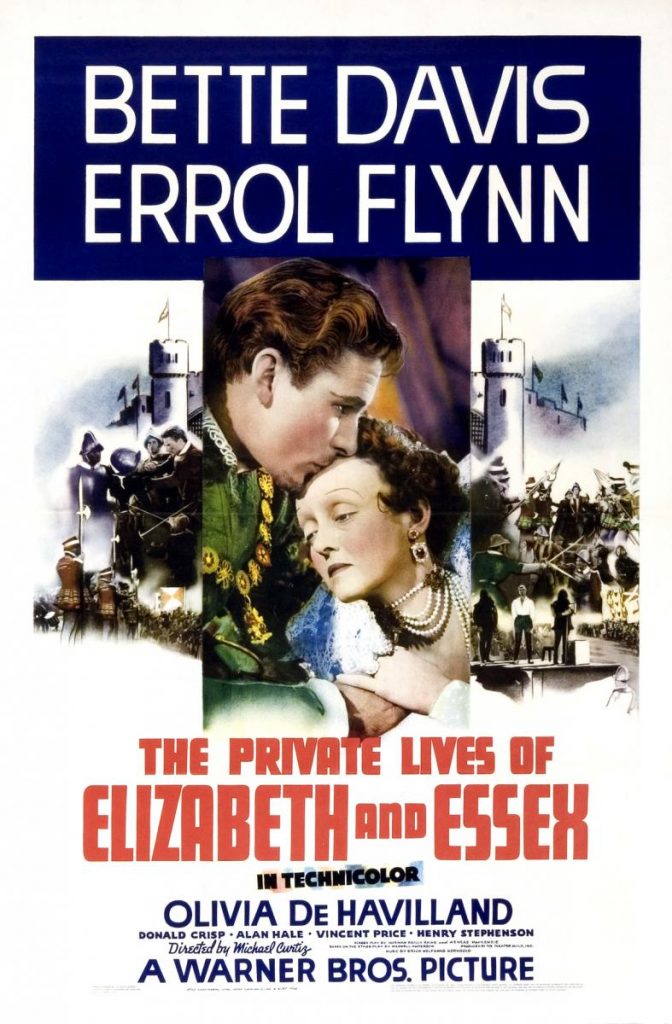

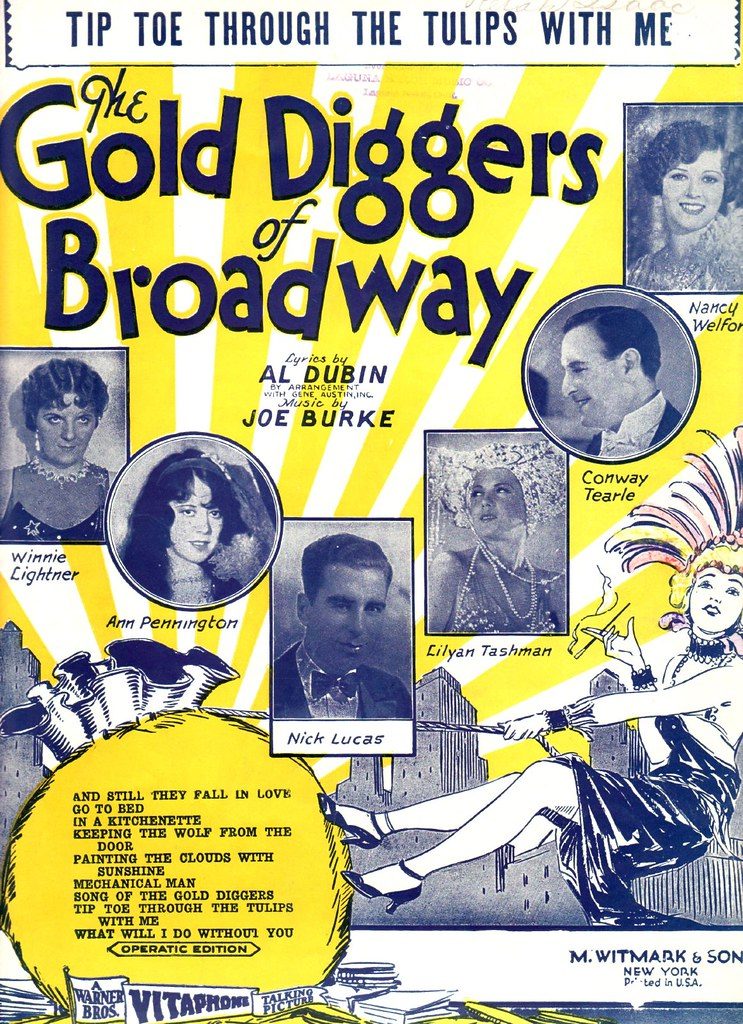

This book offers a different take on the early history of Warner Bros., the studio renowned for introducing talking pictures and developing the gangster film and backstage musical comedy. The focus here is on the studio’s sustained commitment to produce films based on stage plays. This led to the creation of a stock company of talented actors, to the introduction of sound cinema, to the recruitment of leading Broadway stars such as John Barrymore and George Arliss and to films as diverse as The Gold Diggers (1923), The Marriage Circle (1924), Beau Brummel (1924), Disraeli (1929), Lilly Turner (1933), The Petrified Forest (1936) and The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939).

Some extracts:

You may have gathered from the rather long-winded title of this book that you are about to be told a story, an old and familiar one. The story of how the four sons of a Jewish cobbler from Poland created one of the most successful companies in the USA during the twentieth century has been told many times. The Warner Brothers story is one of best stories to come out of Hollywood. As with all good stories, it can be retold in different ways by different people. This book is an attempt to retell that story by concentrating specifically on how this film studio maintained close links with Broadway theatre from 1923. This story is less concerned with Harry, Albert, Sam and Jack Warner, the four brothers behind the company, than with the actors they brought from Broadway in the 1920s and 1930s to make motion pictures based on stage plays. [Chapter 1, page 1]

For most of this time [1920s and 1930s], film actors worked without the assistance of acting coaches or dialogue directors, being often left to their own devices in terms of making an effective transition from stage to screen. Yet many actors devised methods for developing characterisation and screen performances, producing work that both impressed the New York film critics and appealed to large numbers of moviegoers across the world. This included John Barrymore, George Arliss, Ruth Chatterton, Leslie Howard and Bette Davis. Although very different actors, they not only all had Broadway experience prior to working at Warners but also employed methods of characterisation and performance associated (at least to some extent) with Modern acting. Their work, therefore, provides insights into the development of screen acting at a critical moment in Hollywood’s history, during and after the transition from silent to sound cinema. [Chapter 1, page 5]

For more on Modern acting, see Cynthia Baron’s book Modern Acting: the Lost Chapter of American Film and Theatre (Palsgrave/Springer 2016): https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/978-1-137-40655-2

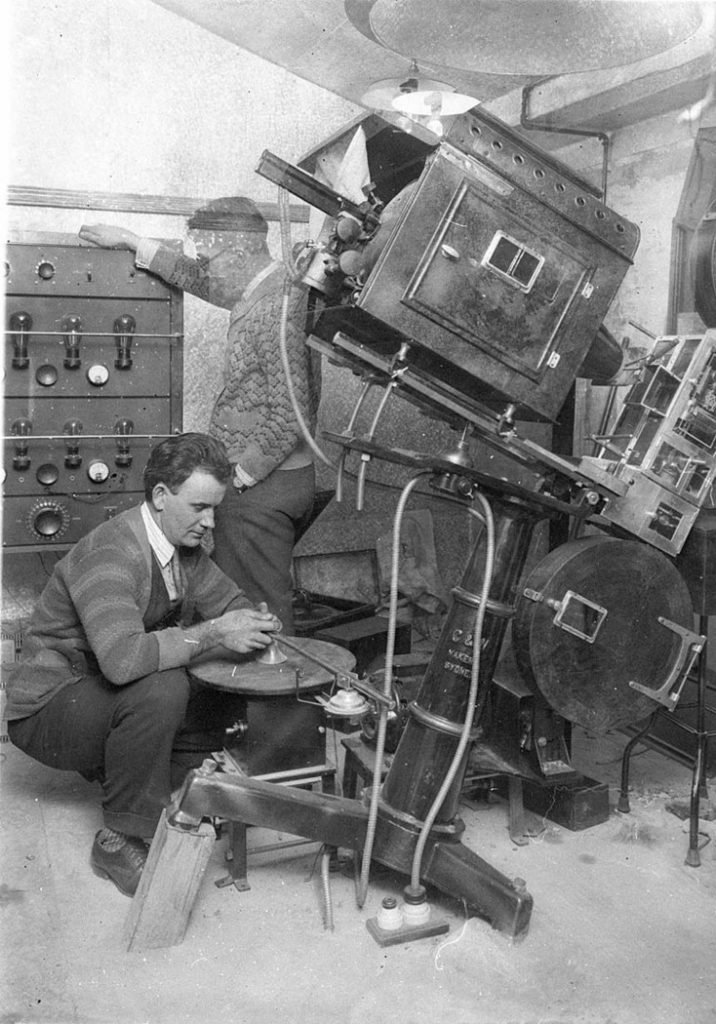

The story of how Warners’ The Jazz Singer revolutionised cinema in 1927 is particularly well known and hardly warrants another book length study. Yet the account of how this film originated from a deep desire by Harry Warner to make films based on Broadway plays featuring stars of the stage provides another perspective, one that situates the “coming of sound” narrative into a larger tale. The story of how sound subsequently impacted upon the practice of acting and direction in Hollywood, first in the early talking picture era of the late 1920s and then during a more mature phase in the 1930s, also marks a departure from the more familiar narrative of how sound created new genres and stars. Here, I shall contend that Warners’ drive to be the first Hollywood studio to develop sound can be better understood within the context of the company’s ambition to bring Broadway players and plays to moviegoers around the world, enabling actors to recreate stage performances more fully and for stage plays to be transferred to the screen with much of the original dialogue intact. [Chapter 1, page 6]

Chapter 1 of When Warners Brought Broadway to Hollywood, 1923-1939 can be accessed and downloaded from here: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-40658-3_1

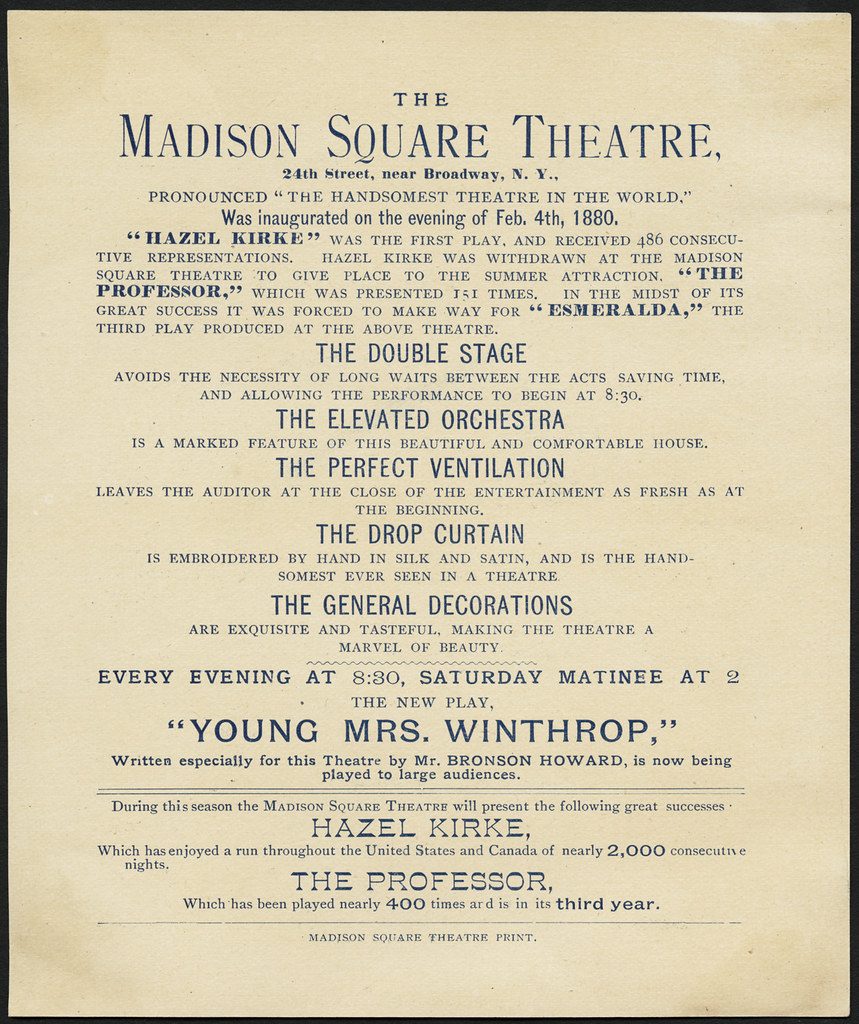

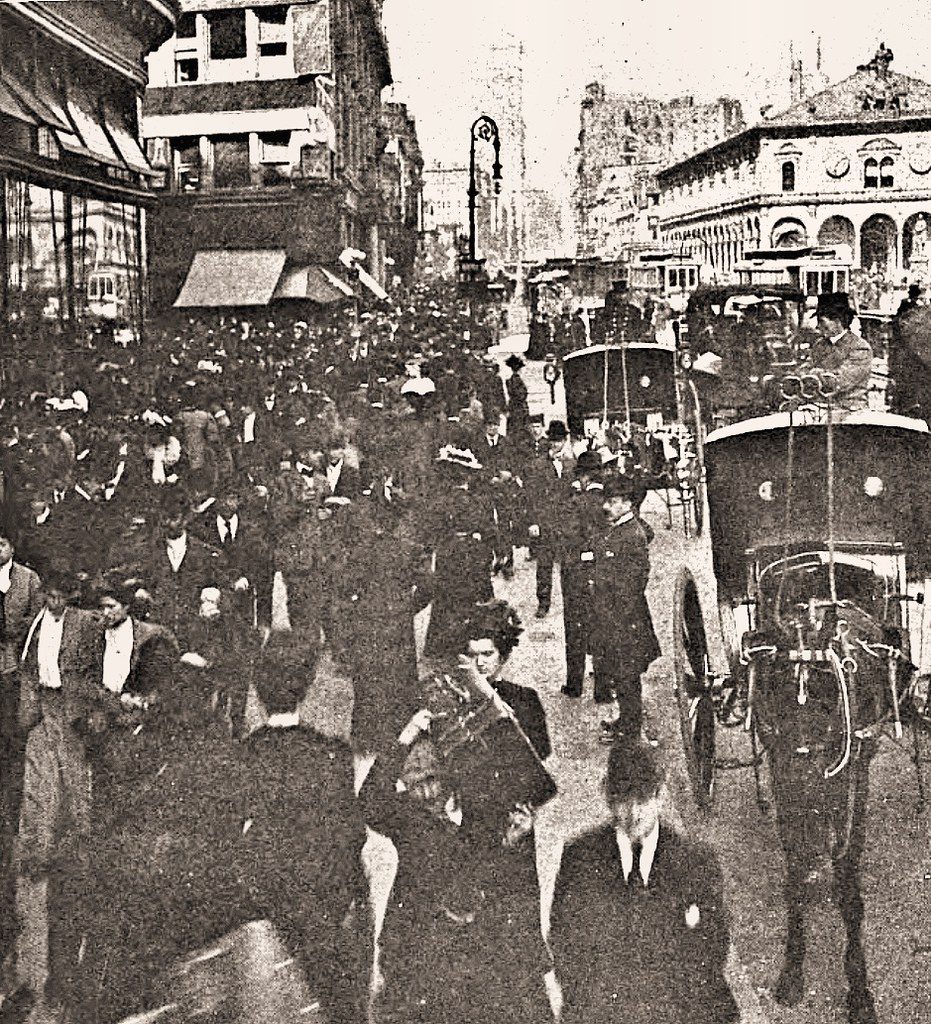

By 1880, Broadway was not only a bustling street that snaked its way through Manhattan in defiance of the city’s more rigid grid system, but it was also a place, one demarcated by the presence of numerous theatres catering to different social groups and tastes. Most of these were located between 13th Street and 42nd Street, including the Union Square Theatre on 14th, the Madison Square Theatre on 24th, Daly’s Theatre on 30th, the Casino Theatre on 39th and the Broadway Theatre at 41st. [Chapter 2, page 21]

Between 1900 and 1920, over fifty new theatres opened in New York, more than doubling the number of legitimate theatres. Meanwhile, the number of annual productions in New York City increased from 87 in 1899-1900 to an all-time high of 254 in 1927-1928. Although the 1927-1928 Broadway season witnessed a marked decline in theatre attendance as a result of the phenomenal popularity of talking pictures, most notably Warners’ The Jazz Singer starring Al Jolson, legitimate theatre houses in New York City enjoyed unrivalled prosperity throughout the first two decades of the twentieth century. [Chapter 2, pages 24-25]

Consequently, Broadway remained the dominant force in American mass entertainment throughout most of the 1920s, despite facing increasing competition from Hollywood, on the one hand, and radio, on the other. Broadway as a whole was still thriving as a dynamic and multifarious entertainment industry in 1920, one that produced farces, Shakespearean tragedies, vaudeville, European art theatre, musical revues, burlesque and girly shows, among other things. [Chapter 2, page 26]

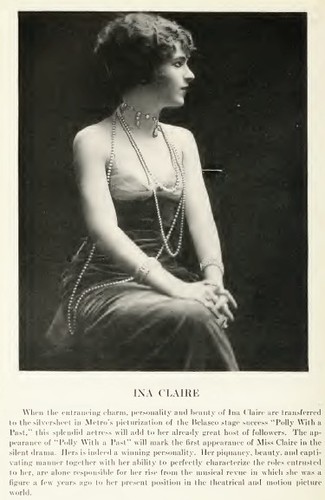

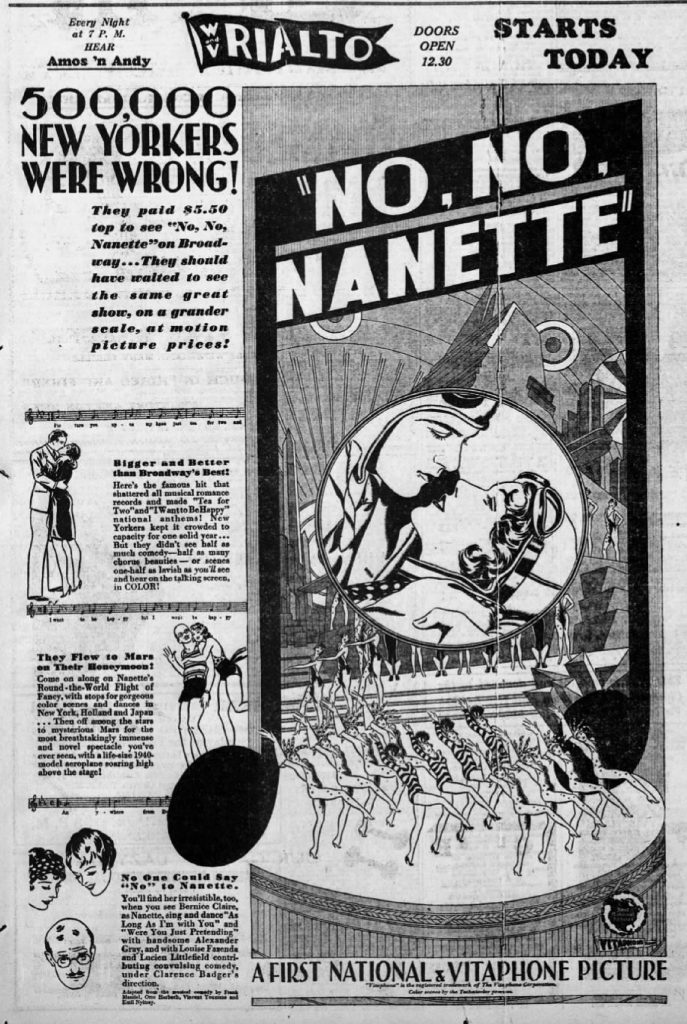

By the late 1910s, the only genre more popular on Broadway than the sex farce was musical comedy. Fast-paced narratives featuring pretty heroines luring rich men to their bedrooms proved to be a winning formula for attracting large numbers of theatregoers and ensuring profitable runs. Audiences delighted in the spectacle of protagonists forced into a series of comical compromising situations that involved them hiding from wives or fiancees under beds and in cupboards, wardrobes and trunks. Such plots were the mainstay of popular entertainment on the American stage during and after World War II, partly … as a consequence of theatre producers having to compete with cinema by adopting a format that was relatively inexpensive to produce and yet had widespread appeal. [Chapter 2, pages 31-32]

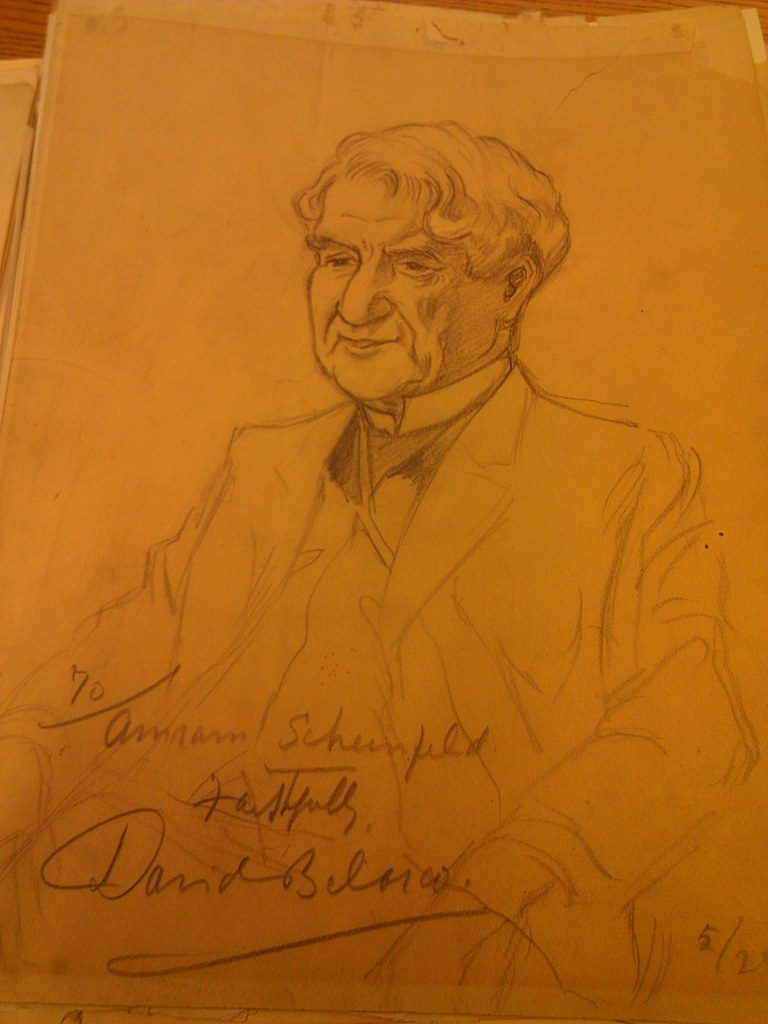

The year 1923 proved momentous for Warners and not only because the company’s president [Harry Warner] persuaded David Belasco to allow his family-run firm to produce several of the producer’s biggest Broadway hits. After officially becoming Warner Bros., the company shifted its production of motion pictures to newly constructed studios on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, where Harry Rapf was promoted to the position of Production Manager. Other significant appointments were made at the same time. In the same year that Hal B. Wallis was hired as a junior in the publicity department, Warners acquired its first major film star, a German Shepherd called Rin Tin Tin. [Chapter 2, page 34]

During the 1920s, Broadway remained the dominant force in American mass entertainment …. For most of this decade, Broadway was buzzing and millions of Americans were eager to experience it. Many Hollywood studios discovered that one of the advantages of making movies based on well-known stage plays was that these were effectively pre-sold on Broadway, raising the interest of much larger group of people than those able to attend New York theatres. [Chapter 2, page 39]

Harry Warner acquired the rights to numerous plays and novels, while staff writers created stories with suitable roles for the likes of Louise Fazenda, Marie Prevost and Monte Blue. During the early to mid-1920s, these actors were able to employ their distinctive personalities and acting styles in Warner photoplays. Many were even able to hone their craft as prestige players through experience, instruction and guidance from some of the world’s most talented director’s …. [Chapter 2, page 41]

Chapter 2 can be downloaded from the Springer website: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-40658-3_2

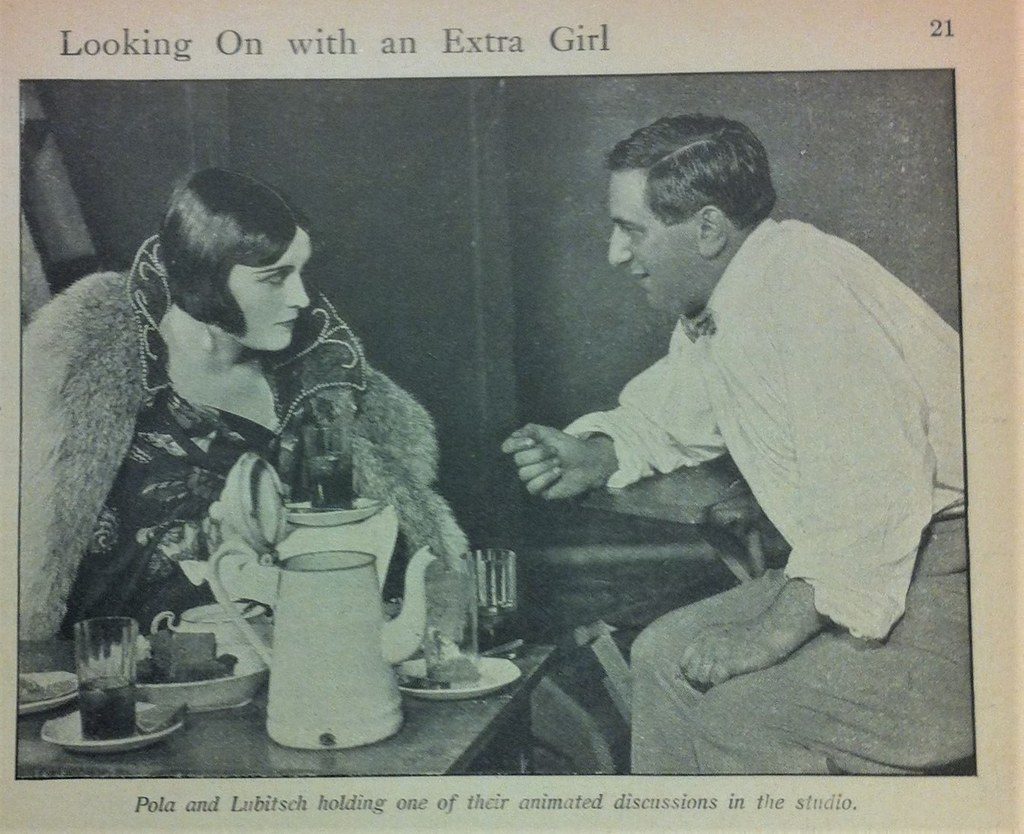

In 1923, after forming an important association with Broadway’s most established producer David Belasco …, Warner Bros. hired Germany’s leading film director Ernst Lubitsch. The association with Lubitsch was a major factor in the company’s ongoing transformation into one of the world’s most important film studios. [Chapter 3, page 51]

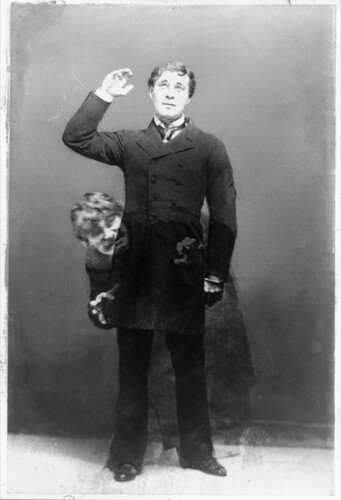

By 1920, acting on the American stage had become much more subtle, individualistic and naturalistic than in the previous century. The days were long gone since actors performed in a self-consciously theatrical style with an ostentatious or “bravura” (that is, showy, florid, ornate or grandiose) performance in order to elicit applause, cheers and encores from the audience. Indeed, proud displays of acting prowess that involved actors facing the audience at the front of the stage, delivering their climactic speeches while making points had become associated with hams rather than great actors by the late nineteenth century. [Chapter 3, page 63]

A leading exponent of Modern acting, Mrs. Fiske concentrated on inner feeling and restrained expression, studying her parts in order to fully understand her character’s intentions, thought and emotions. [Chapter 3, page 65]

Mrs Fiske’s acting method involved an intellectual and cool-headed approach, with every movement, gesture and expression being meticulously worked out in advance and adhered to during the performance. Detailed research, preparatory work and careful construction of characters based on script analysis were fundamental to her method. Her acting not only epitomised new trends on Broadway in the early twentieth century but also corresponded to much of the teaching at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, established in 1892. [Chapter 3, page 66]

… many of the actors trained at New York acting schools and academies inevitably found their way into film acting, performing alongside actors with either very different training or even, in some cases, no training at all. [Chapter 3, page 67].

Many [film performers] were inexperienced when it came to acting in silent films in the 1910s, and their attempts to judge the appropriateness of gestures (in scale, speed and direction) were complicated by their unfamiliarity with the medium. As screen actors made their film debuts at different times, hard and fast chronologies of acting in Hollywood prove unsustainable, with emphatic and histrionic acting remaining observable in many films made after 1915. [Chapter 3, page 66]

Actors who had previously performed in more emphatically gestural ways certainly proved their versatility when working with Lubitsch at Warners in 1924. Marie Prevost’s naturalistic underplaying in The Marriage Circle seems all the more impressive given that at Keystone in the late 1910s she had evolved a histrionic form of comic acting that was highly gestural and included a considerable amount of exaggerated facial expression, including mugging, well suited to short silent comedy films. [Chapter 3, page 67]

It is clear that by 1924 Marie Prevost was capable of conveying subtleties and subtext as part of her silent screen performances with an understated naturalism far removed from the more telegraphic gestures and facial expressions of her Keystone days. It is also clear that Lubitsch respected her as an actor, given that he subsequently worked with her again on two more occasions. [Chapter 3, page 68]

For more on Prevost’s performance in The Marriage Circle and Lubitsch’s time at Warner Bros., see Chapter 3: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-40658-3_3

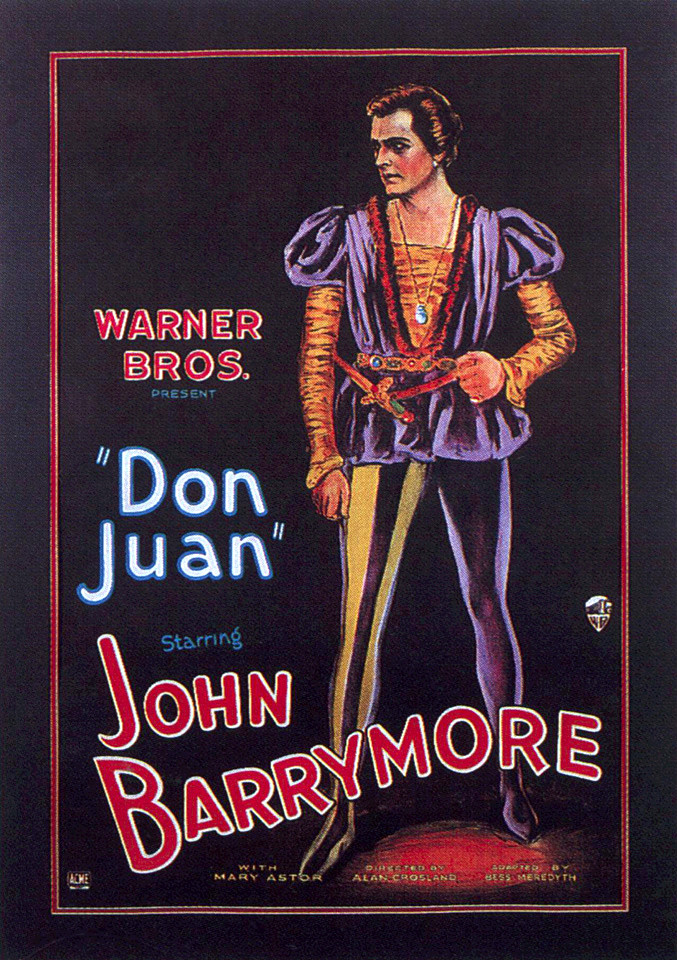

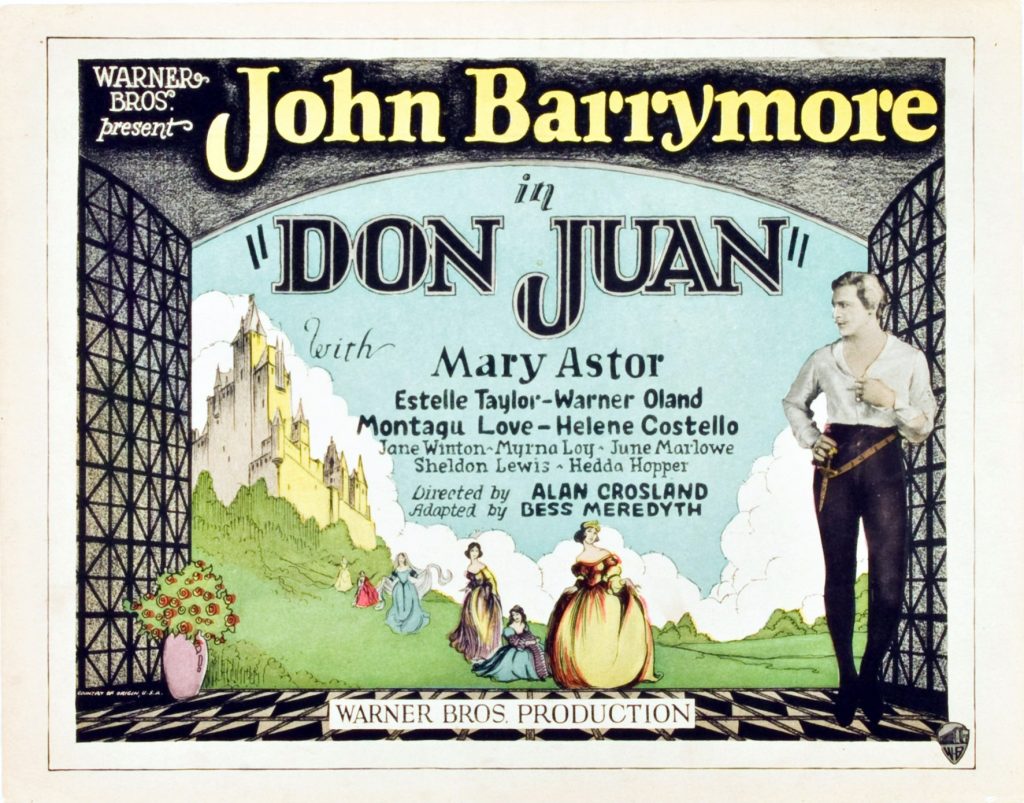

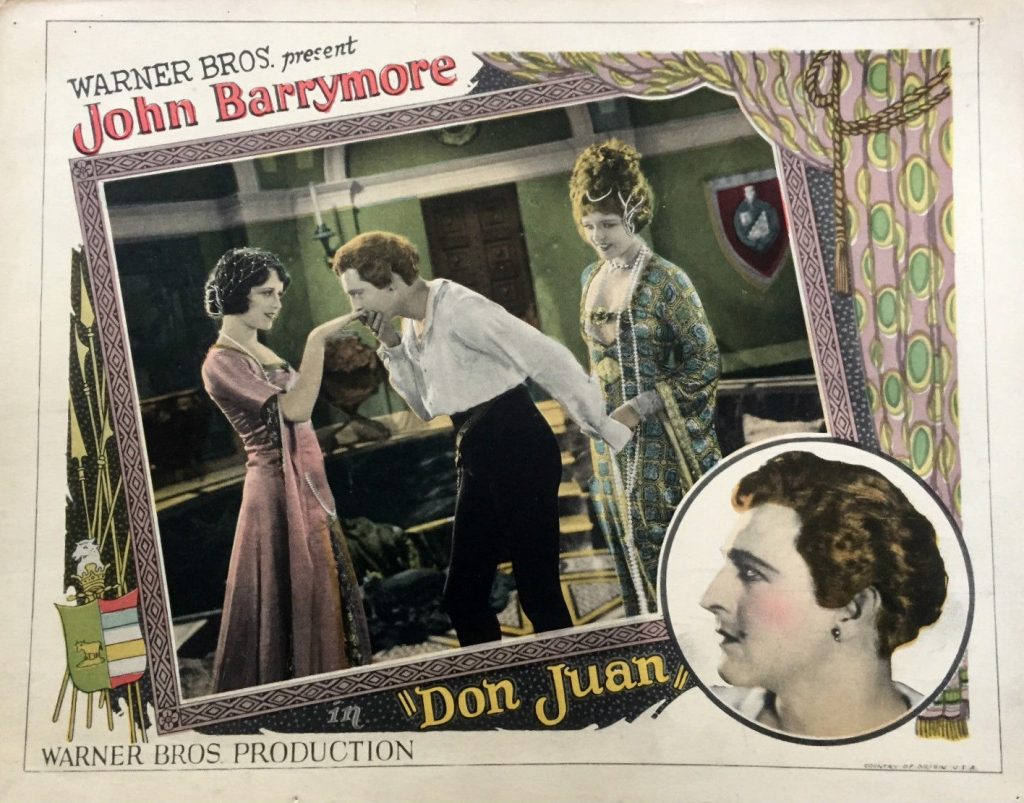

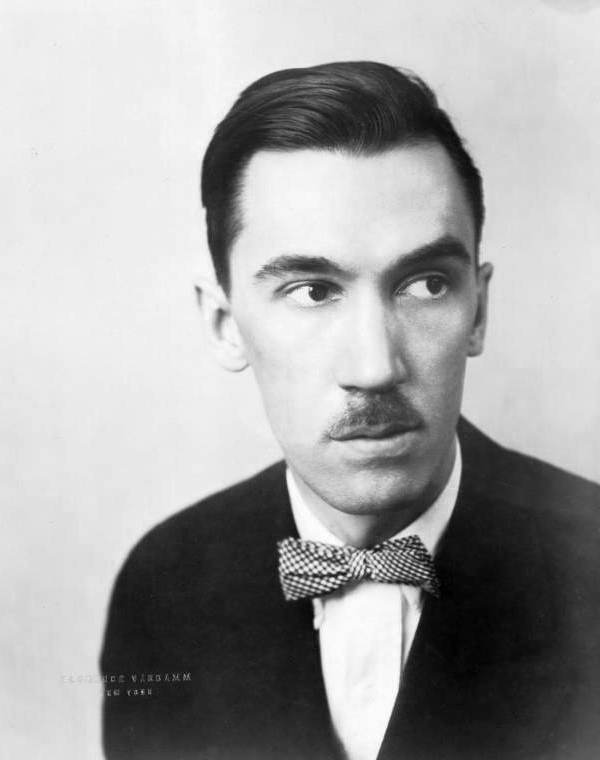

When Warner Bros. recruited John Barrymore in 1924 to star in a silent screen adaptation of Clyde Fitch’s stage play Beau Brummel, the company acquired the services of America’s most celebrated actor, one with a considerable pedigree. This added significantly to the studio’s status, especially when Barrymore signed a more permanent contract, under which he appeared in another nine films at Warners over the next 8 years. Many of these capitalised on his good looks, acting talent and star image, some receiving rave reviews from the New York film critics and others earning large profits at the box office. [Chapter 4, page 80]

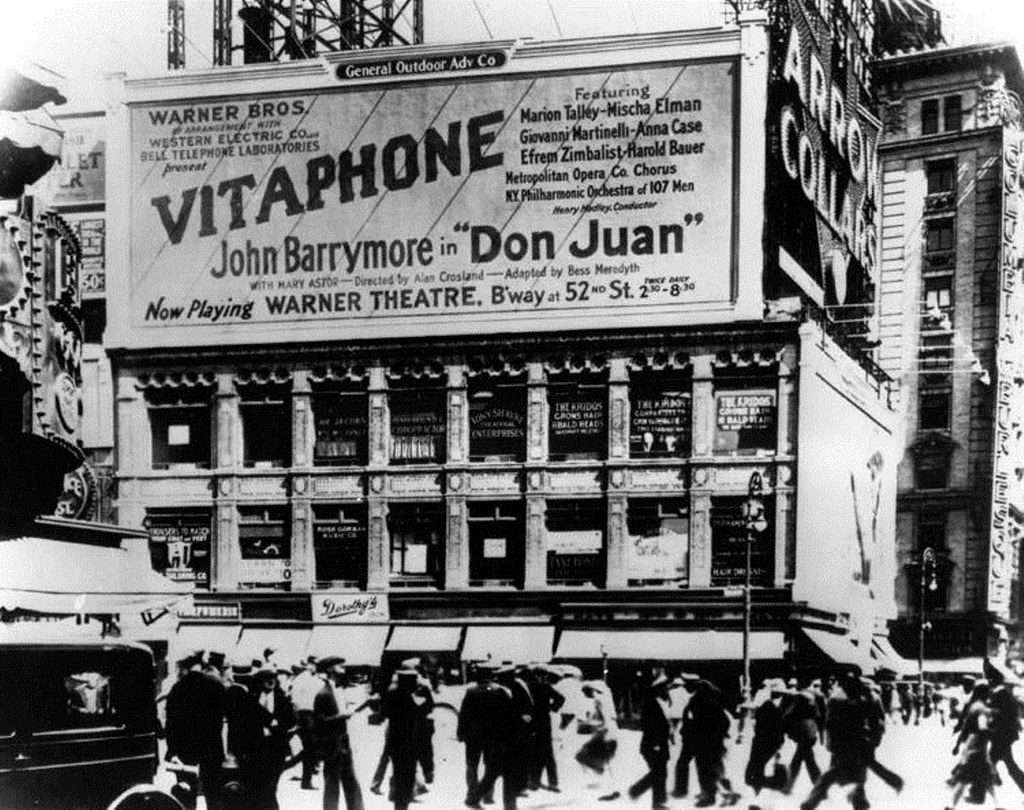

Although hired as a prestigious actor in 1924, Barrymore had become one of Warners’ most profitable film stars by 1926, proving that prestige pictures and theatrical films could be highly profitable at the box office. This was certainly the case when Warners released Don Juan, a film that cost $546,000 and grossed a total of $1,693,000. [Chapter 4, page 89]

Based on the play that Richard Mansfield had adapted from a poem by Lord Byron and first staged in 1891, Don Juan was transformed by a team that included director Alan Crosland and screenwriter Bess Meredith into an energetic swashbuckling adventure film that harks back to the Neo-Romanticism of the late nineteenth-century stage. [Chapter 4, page 89]

Having selected Don Juan as the film to launch Vitaphone [the sound-on-disc system], the publicists at Warners went to great lengths to stress the film’s attractions for both male and female moviegoers. [Chapter 4, page 90]

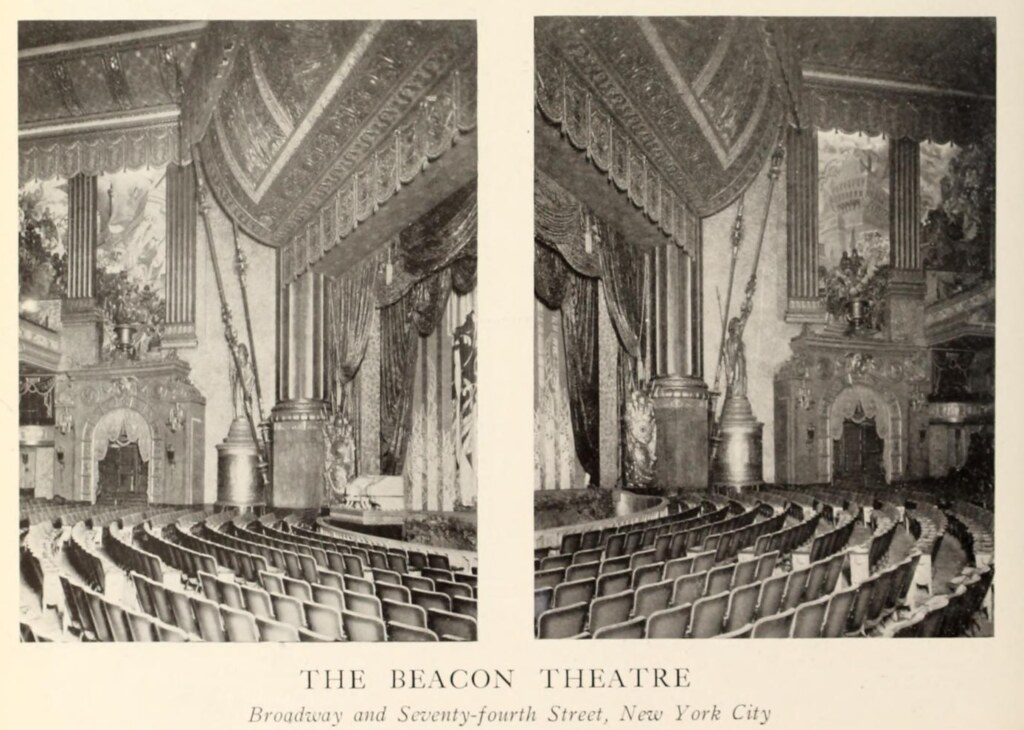

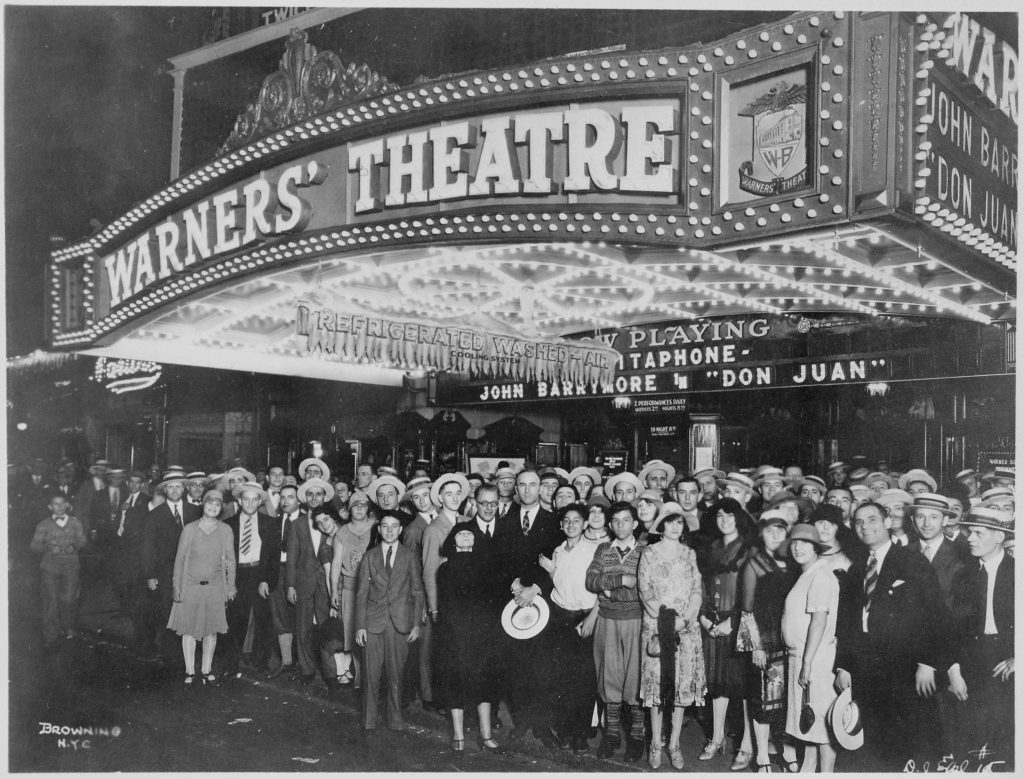

Don Juan had all the hallmarks of a prestige picture in 1926, featuring not only America’s most distinguished actor but also the New York Philharmonic, which performed the film’s score for the recorded soundtrack. At its New York premiere on August 6, 1926 at the Warner Theatre on Broadway and 52nd Street, Don Juan formed part of an elaborate programme that included a series of sound shorts, some featuring the stars of the Metropolitan opera. The programme had a successful run of 8 weeks in New York City and was reportedly seen by over half a million people before achieving record-breaking runs throughout the USA and many parts of Europe. [Chapter 4, page 91]

To find out more about Don Juan and Barrymore’s other Warner photoplays, see: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-40658-3_4

During the early years of talking pictures, Broadway talent was much sought after in Hollywood. Warner Bros. was in such a good position as the leading producer of sound films in the late 1920s that the company was able to recruit the very best of Broadway. After Wall Street crashed in October 1929 and theatregoing in New York declined rapidly, many Broadway stars looked to Hollywood for gainful employment, and a significant proportion of these headed to Warners to perform in musicals and prestige pictures based on stage plays. [Chapter 5, page 105]

When the sixty-year old George Arliss signed a three-picture contract with Warner Bros. in August 1928, he began an association with the company that lasted for almost five years. During that time, while making ten films for the studio, he established a company of actors, some of whom he had previously worked with on the American stage, while others were Warners’ contract players with stage experience in summer stock and supporting roles on Broadway. [Chapter 5, page 106]

It was in 1928 when the actor was playing Shylock in William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice at the Broadhurst Theatre that the movie mogul [Harry Warner] persuaded Arliss to make talking picture versions of his stage hits at Warners. [Chapter 5, page 107]

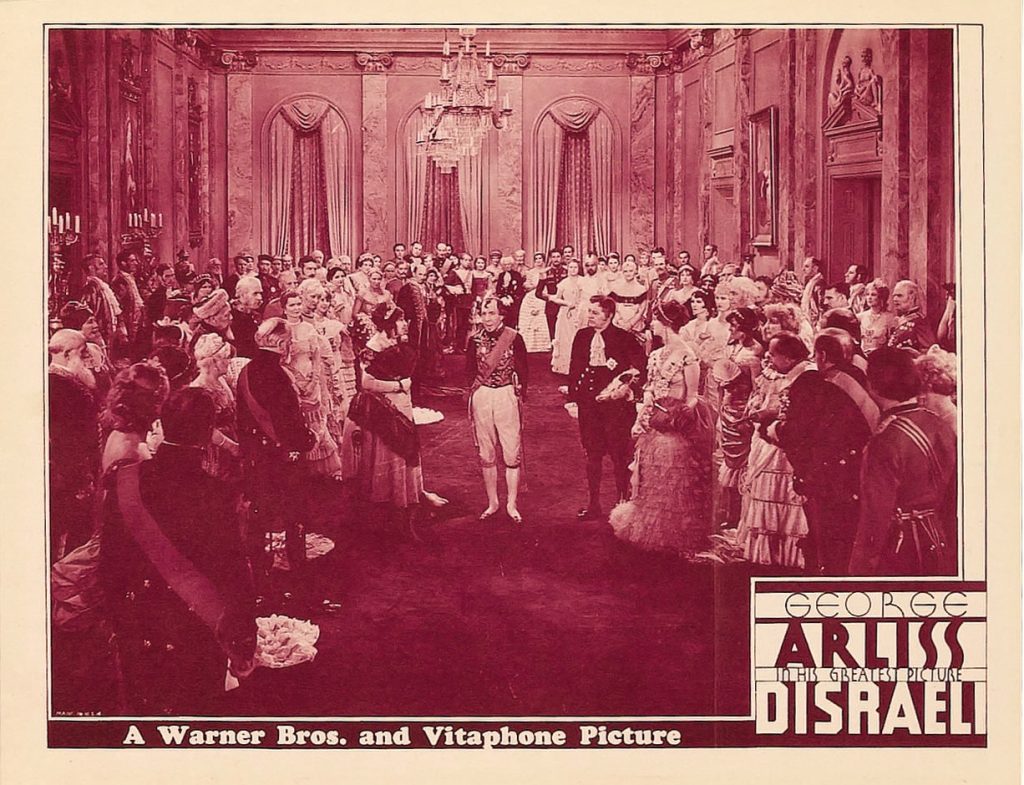

Arliss was subsequently hired to make three films for a total of $100,000. These were all based on his biggest stage hits, The Green Goddess, Disraeli and Old English, which were filmed in that order in 1929, even though Disraeli was released first. [Chapter 5, pages 107-108]

Warners’ sound version of Disraeli not only benefitted from George Arliss’ long and intimate acquaintance with the play and his director’s sensitivity, but also from an impressive cast that featured many British actors, combining experienced players with some new faces. Between them, the British actors David Torrence, Doris Lloyd and Ivan F. Simpson provided a wealth of experience on Broadway and in Hollywood. [Chapter 5, page 109]

In contrast, Joan Bennett was a relative novice when she joined the supporting cast of Disraeli, having had some recent Broadway and Hollywood experience supporting her father Richard Bennett…. [Chapter 5, page 110]

In March 1930, shortly after Arliss won his Oscar for Disraeli, Warners extended his contract for a further four pictures, offering him $125,000 for three films, with an option to make a fourth film for £41,000. Throughout 1930, Arliss films remained financially viable, having earned an impressive total of $904,000 for Warners by the spring of 1931. Consequently, the studio was in a good position at this time to increase his salary. Also, despite the Depression and soaring levels of unemployment across the USA in 1930, Warner Bros. was able to increase its average budget per film from $306,500 in 1929-1930 to $354,300 in 1930-1931 due to increased cinema admissions and box-office revenue. [Chapter 5, page 121]

Maude Howell, Julien Josephson and John G. Adolfi were leading members of the Arliss unit at Warners in the early 1930s, as were the cinematographer James van Trees, the art directors Anton Grot and Esdras Hartley and editor Owen Marks. Arliss’ wife, Florence, was part of a group of actors who appeared regularly with him, constituting the Arliss company. None worked exclusively on Arliss films but all were frequently drafted to work on one Arliss production after another during the early 1930s. This team of Arliss regulars enabled a coherent and consistent film cycle to emerge at Warners in the early 1930s, one that bore the star’s name. [Chapter 5, page 122]

At a transitional time in Hollywood history, Arliss proved that stage and screen acting had much in common and that stars of the English and American theatre could become some of the most acclaimed and popular stars in Hollywood. In his early sixties, Arliss also proved that old age was no barrier to Hollywood success. His films provided regular and lucrative work for accomplished and experienced veterans such as David Torrence and Ivan Simpson, while nurturing and refining the talents of newcomers such as Joan Bennett, Anthony Bushell and Bette Davis. [Chapter 5, page 128]

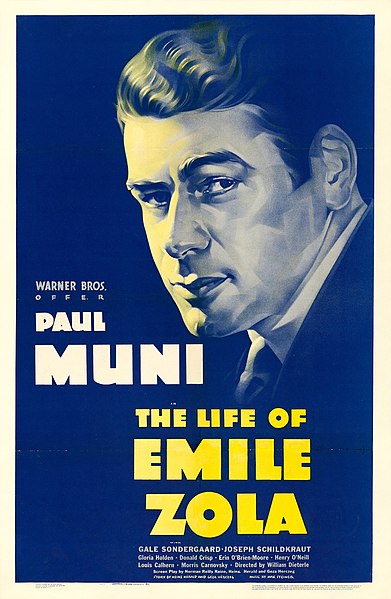

Arliss not only made prestige pictures a fixture at Warners during the early sound era but also paved the way for prestige actors such as Paul Muni and Edward G. Robinson. Perhaps most of all, Arliss proved the commercial viability of the star company mode of production. [Chapter 5, page 128]

Chapter 5 can be accessed here: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-40658-3_5

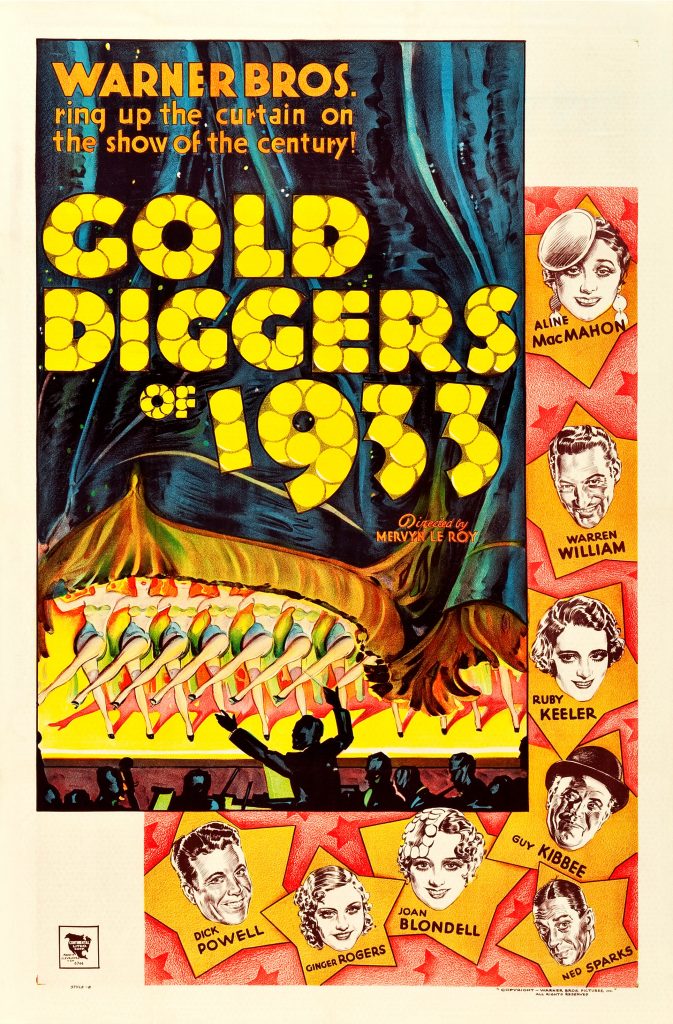

Between 1932 and 1934, Warner Bros. instituted a series of cost-cutting measures that prohibited the production of expensive prestige pictures based on stage plays. While significantly reducing the number of big-budget films, the company mostly replaced star vehicles with ensemble pictures featuring large numbers of popular players on long-term option contracts. Many of these had theatre backgrounds, like Aline MacMahon, Guy Kibbee and Frank McHugh, and performed alongside each other in a steady stream of box-office hits that helped to save the studio from bankruptcy. [Chapter 6, page 135]

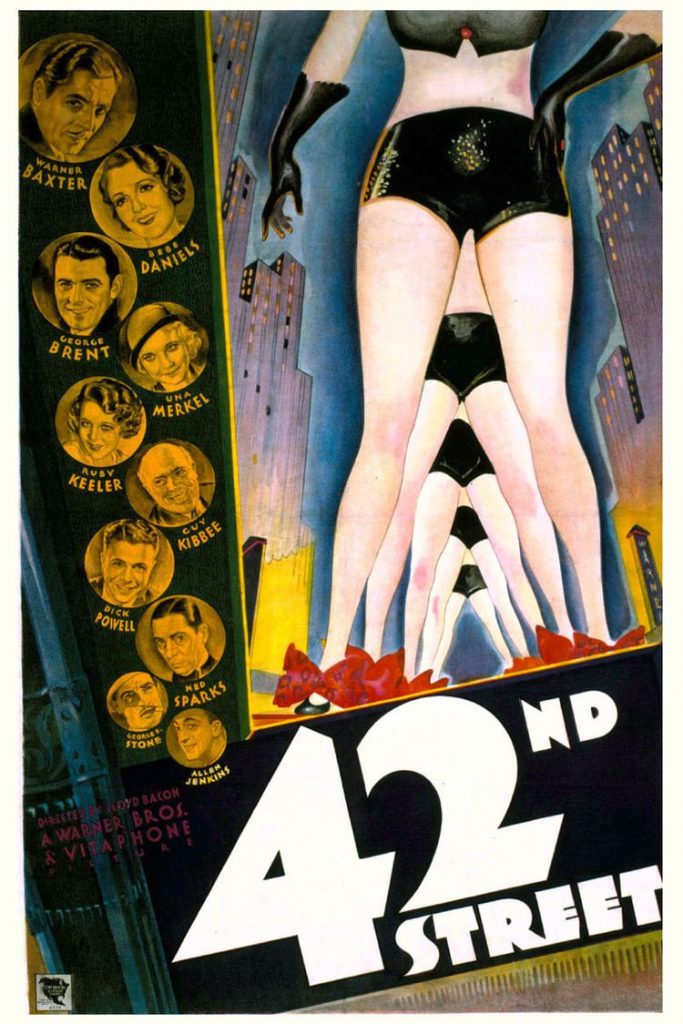

Despite the huge cast, elaborate staging and choreography, the film [Gold Diggers of 1933] was made for just $433,000 and went on to gross an impressive $3,231,000. … [T]he success of 42nd Street [Bacon & Berkeley 1933]and Gold Diggers of 1933 led to more ensemble musicals like Dames (Enright 1934), which cost $779,000 and grossed $1,513,000. In general, these proved more profitable than gangster films starring James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson. In addition to being set in New York’s theatre district, many of these backstage musical comedies featured cast members drawn from the Broadway theatre. [Chapter 6, page 137]

[However] … the assumption that Warners favoured ensemble musicals over other genres in 1933 and 1934 because of the high returns of films such as 42nd Street and Gold Diggers of 1933 risks losing sight of the extent to which the studio remained committed to star actors in star vehicles. [Chapter 6, page 139]

Warners’ ability to retain star actors on high salaries was jeopardised in 1933 and 1934 due to increasing financial loses. Nevertheless, stars remained crucial to Warners’ survival during this period. Alongside the genre system, stars were used to stabilise a notoriously unpredictable market for films. Films with established stars (more especially, those with large numbers of fans) could be sold to distributors at higher rates and exhibited in first-run theatres that sold seats at the highest prices, generating greater returns. As films based on successful novels and stage plays could also be sold at higher rates and shown in high-priced theatres, the combination of a popular star with a photoplay pre-sold on Broadway increased the chances of a high rate of return. [Chapter 6, pages 139-140]

The development of mixed portfolios of star vehicles enabled major studios like Warner Bros. to earn significant profits from their most popular stars, even if one or two failed to break even at the box-office each year. Stars would ordinarily have the options of their contracts renewed annually (along with the pay increases agreed at the time of signing their contracts) if their portfolio of star vehicles remained profitable overall. [Chapter 6, page 140]

It was a significant achievement for Warner Bros. to recruit Ruth Chatterton on January 12, 1932, since she was Paramount’s top female star. At Paramount Chatterton had earned Oscar nominations for her performances in the maternal melodramas Madame X (Barrymore 1929) and Sarah and Son (Arzner 1930) and had become known as the “First Lady of the Screen.” Exuding glamour and sophistication, she created a series of risqué roles opposite many of the studio’s leading male stars. Yet Chatterton’s status as Paramount’s leading lady was also due to her Broadway credentials, including her tutelage by the the highly respected Henry Miller from 1912 to 1925. [Chapter 6, pages 140-141]

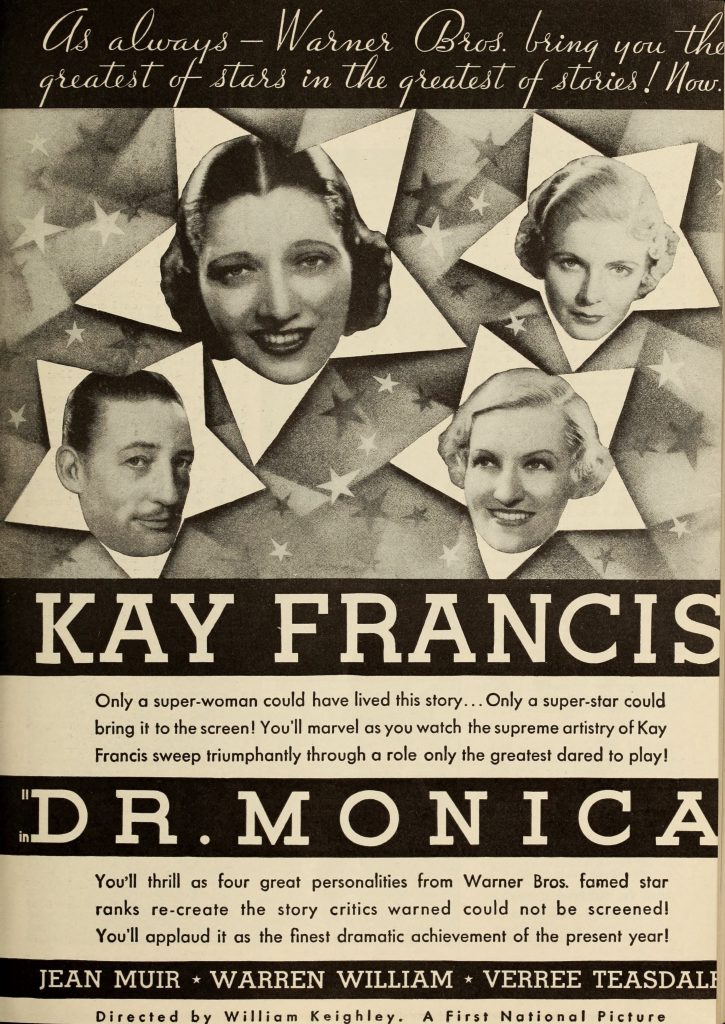

With such a distinctive and distinguished image, as well as a string of hit plays and films to her credit, Chatterton was able to command favourable terms at Warners in January 1932. She not only secured a starting salary of $8000 a week but gained the right to veto any screenplay, director or leading man that she did not approve of. Under this contract, she made six films for the Warner subsidiary First National Pictures: The Rich Are Always with Us (Green 1932), The Crash (Dieterle 1932), Frisco Jenny (Wellman 1932), Lilly Turner (Wellman 1933), Female (Curtiz 1933) and Journal of a Crime (Keighley 1934). Yet Warners’ attempt to match the commercial success of Chatterton’s Paramount films failed, with none receiving awards or nominations. Few received rave reviews and even the most successful only generated modest profits. [Chapter 6, page 141]

For more on Ruth Chatterton and the films she made at Warner Bros. from 1932 to 1934 (notably, Lilly Turner) see Chapter 6: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-40658-3_6

Warner Bros. was so crippled by the economic effects of the Depression by 1934 that it was struggling to repay the interest on its loans and was forced to instigate a further series of drastic cuts to its budgets. This made the production of prestige pictures almost impossible. Consequently, several major productions had to be abandoned, including a biopic of Napoleon. … In 1934, Warners’ precarious economic circumstances resulted in such projects being replaced by cheaper modern-day genre pictures that could recycle sets and costumes from previous productions, be shot quickly and maintain a small be steady return at the box office. [Chapter 6, page 151]

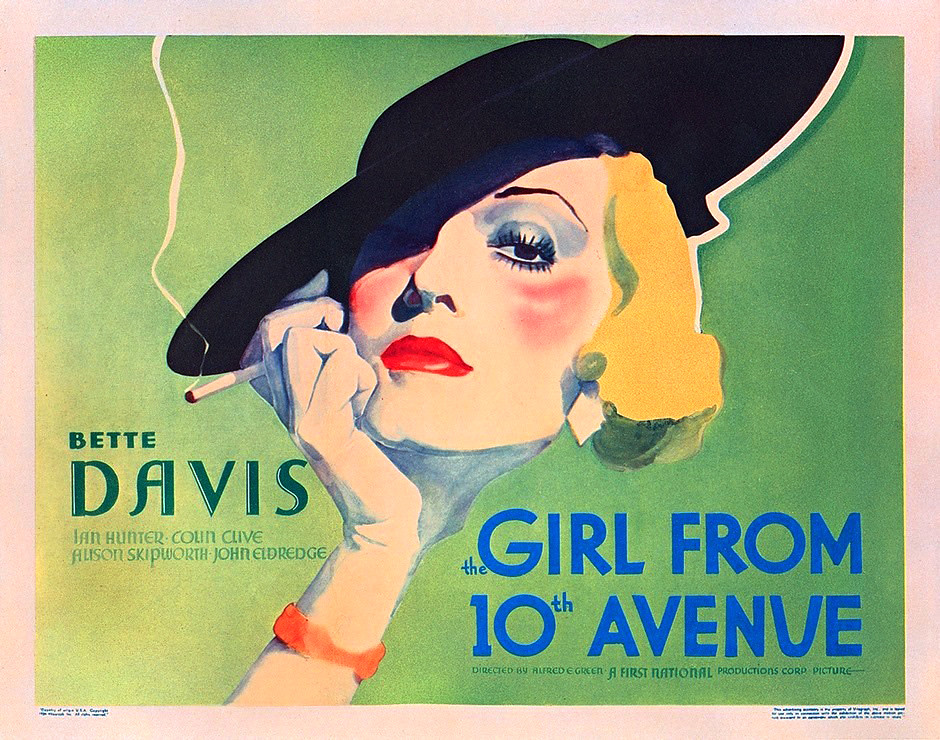

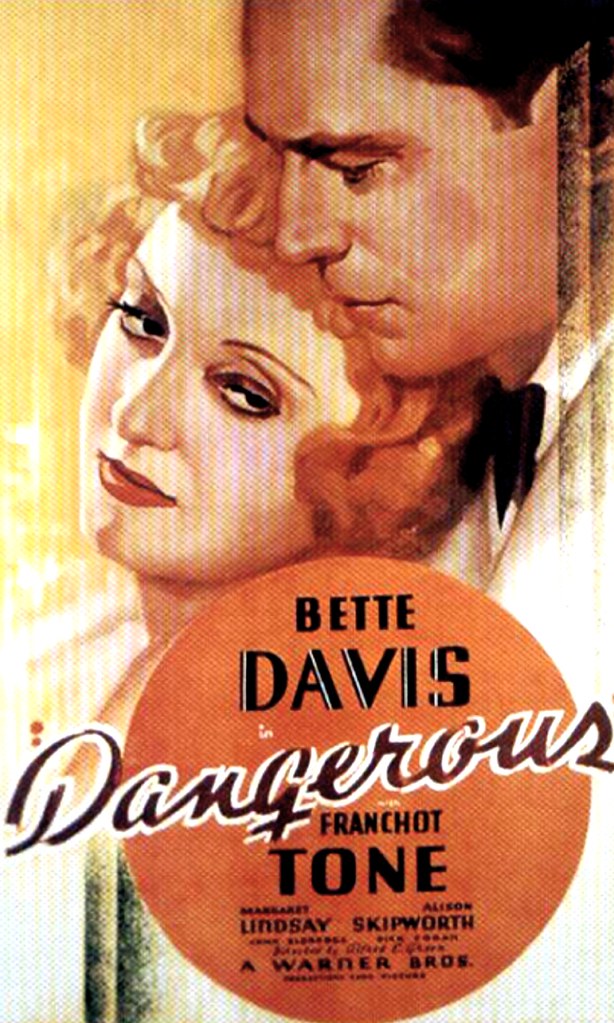

The films of Bette Davis in 1934 and 1935 proved the commercial viability of inexpensive productions at this time. Davis was repeatedly cast in a series of low- to medium-budget crime thrillers, romantic dramas and comedies, supporting James Cagney in Jimmy the Gent (Curtiz 1934) and Paul Muni in Bordertown (Mayo 1935). [Chapter 6, page 151]

However, not only was she given her own star vehicles, including Dangerous (Green 1935), but she was also frequently paired with Ruth Chatterton’s former leading man (and current husband) George Brent, the two actors headlining in Housewife (Green 1934), Front Page Woman (Curtiz 1935) and Special Agent (Keighley 1935). At this time, Bette Davis’ movies did consistently well at the box office, with particularly good returns for Bordertown and Dangerous. This meant that when Ruth Chatterton left Warners Bros. in 1934, Davis was well placed to fill her shoes as one of the studio’s leading female actors. [Chapter 6, pages 151-152]

Although Davis’ star vehicle The Girl from 10th Avenue (Green 1935) was not a particularly distinguished film, it did have some of the hallmarks of a prestige picture. Produced by Henry Blanke (Lubitsch’s former assistant), it was directed by Alfred E. Green, who had previously directed George Arliss in Disraeli and Ruth Chatterton in The Rich Are Always with US. Moreover, it was based on a stage play by Hubert Henry Davies and, in addition to the British actor Ian Hunter in the supporting cast, included [Broadway actresses] Katharine Alexander and Alison Skipworth. [Chapter 6, page 152.

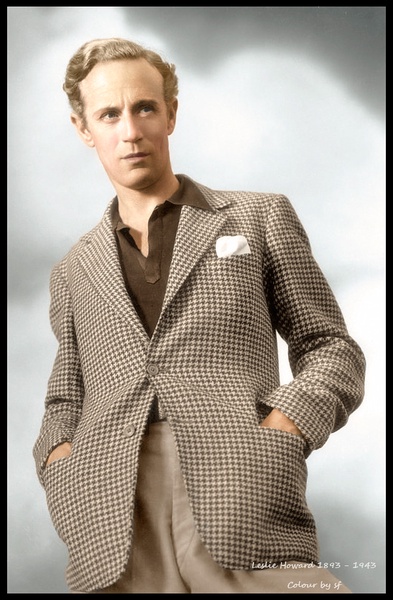

When Warner Bros. revived the production of prestige pictures in 1935, it had to replace those stars who had departed in 1933 and 1934, such as George Arliss and Ruth Chatterton. Consequently, Paul Muni, Leslie Howard and Bette Davis were cast in some of the studio’s most prestigious productions. While William Dieterle directed Paul Muni in the biopics The Story of Louis Pasteur and The Life of Emile Zola (1937), Archie Mayo directed Leslie Howard and Bette Davis in The Petrified Forest (1936). [Chapter 6, page 153]

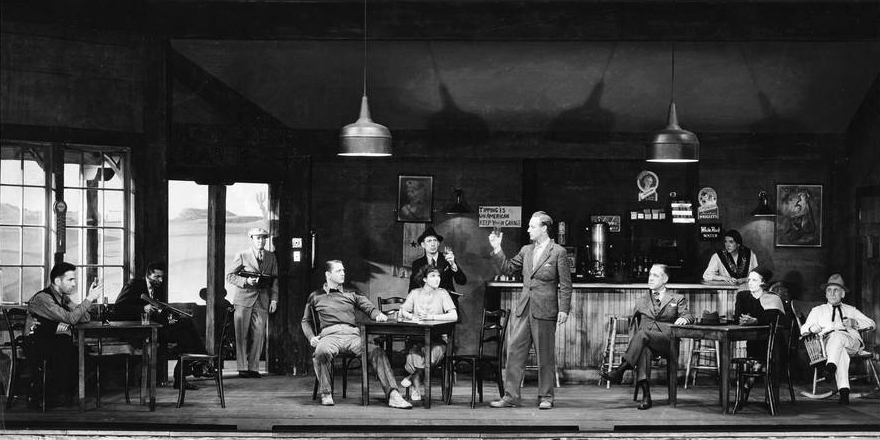

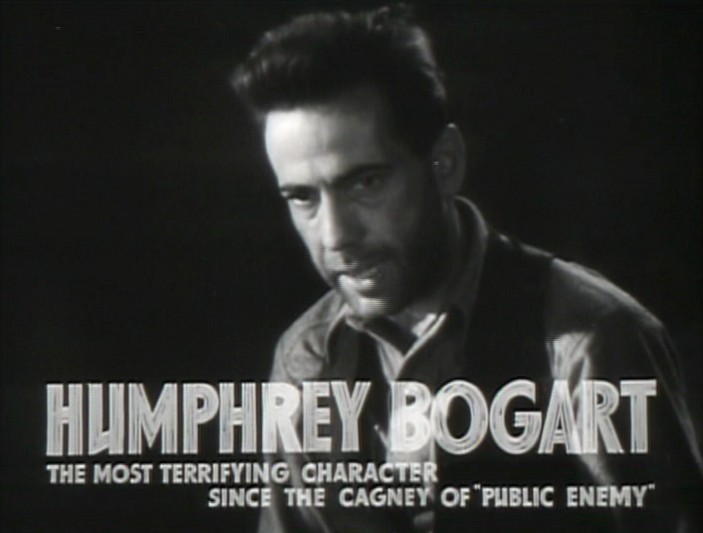

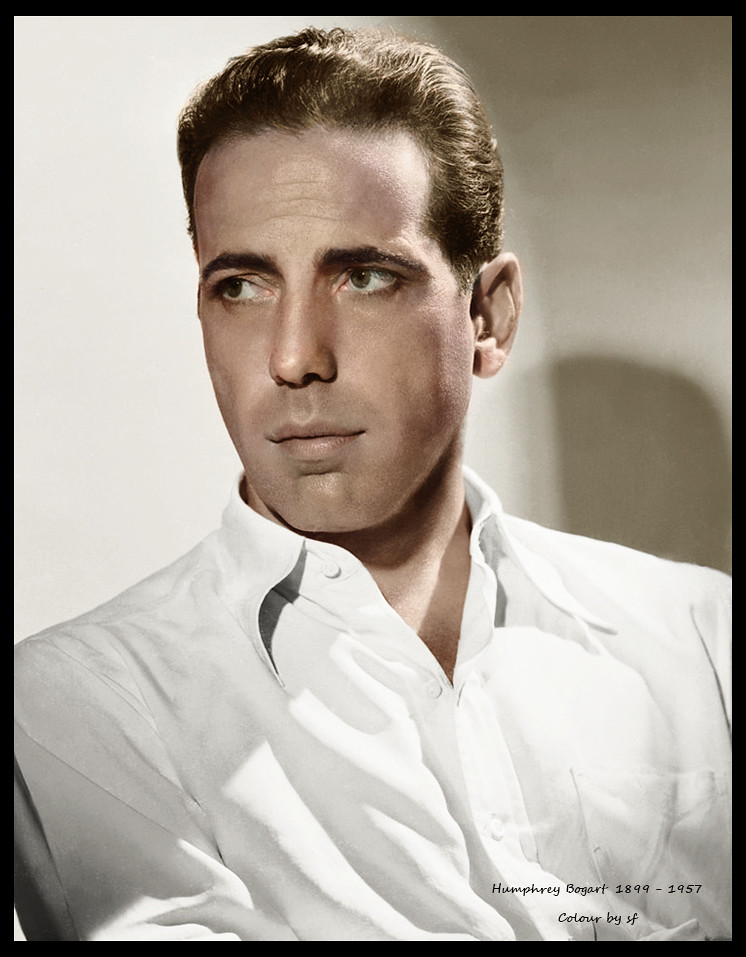

It would be all too easy to mistakenly identify The Petrified Forest (Mayo 1936) as a classic Warners’ gangster move starring Humphrey Bogart as a vicious mobster hunted by the law, with a tragic romantic subplot featuring a young Bette Davis and a middle-aged Leslie Howard. [Chapter 7, page 163]

A faithful adaptation of a successful Broadway stage play written for, starring and co-produced by Leslie Howard in 1935, it was actually a Howard star vehicle, designed to exploit the actor’s distinctive image and acting style. [Chapter 7, page 163]

In essence, it is an allegorical and philosophical drama about a small yet diverse group of people trapped in a roadside diner in the middle of the desert. As such, it deals with themes of activity versus passivity, ambition versus hopelessness, idealism versus cynicism, although its key theme is the possibility of escape versus the inevitability of entrapment. While its main plot consists of a tragic love story (involving romance, humour and pathos, culminating in tears), its subplot forms the basis of a crime thriller involving a desperate group of gangsters on the run after a killing spree. The latter involves jeopardy, suspense and thrilling action, culminating in an exciting gunfight. The carefully interwoven generic tropes of romantic drama, the Western and the urban crime thriller ensured The Petrified Forest widespread popularity among theatre and cinemagoers in the mid-1930s, making it a hit both on stage and screen. [Chapter 7, page 163]

It was in 1933, after moving back and forth between MGM and RKO, that Howard signed a non-exclusive contract with Warner Bros. for three films a year over three years. [Chapter 7, page 167]

Howard was, above all, a naturalistic actor, who performed with a quiet self-assurance and slightly quizzical attitude that lent his characters a degree of self-mockery. Utilising small and individualistic gestures made his performances seem natural and realistic, although a subtle degree of incredulity undermined this to some extent, producing a hint of artificiality. Consequently, despite an absence of grand or emphatic gestures and expressions, there was something quintessentially theatrical about Howard’s subdued performance style, something that intimated to his audience that he was playacting. [Chapter 7, pages 167-168]

… what Howard would have discovered when scrutinising the script [of The Petrified Forest] was a character very similar to himself, given that Robert Sherwood devised Alan Squier to be the perfect part for Howard’s persona and acting style. Sherwood also provided a setting in which Howard’s character would seem incongruous, thereby accentuating his individuality, including his bemusement, passivity and detachment. At the same time, he devised a strong supporting cast of characters who either complemented or contrasted with the central protagonist, further highlighting his distinctive qualities. [Chapter 7, page 168]

Adapted by Charles Kenyon and Delmer Daves, the screenplay of The Petrified Forest stuck closely to Robert Sherwood’s original script. All the characters were retained, apart from the references to the fictitious Warner Bros. screenwriter Sidney Wendell. Much of the original dialogue also survived, with the exception of the word “gigolo,” which, although mentioned twice in the play, is never mentioned in the film, presumably to avoid any conflict with the Production Code. [Chapter 7, page 173]

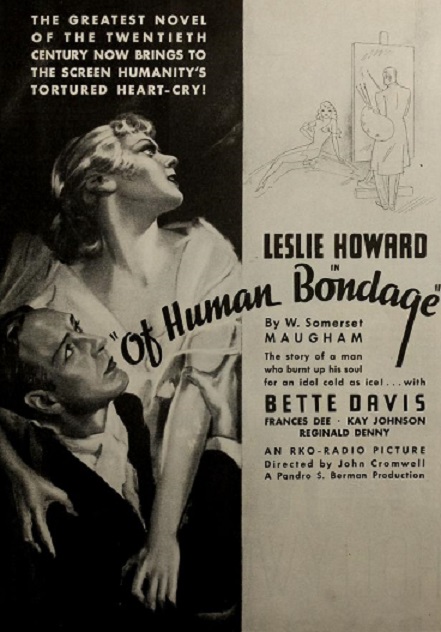

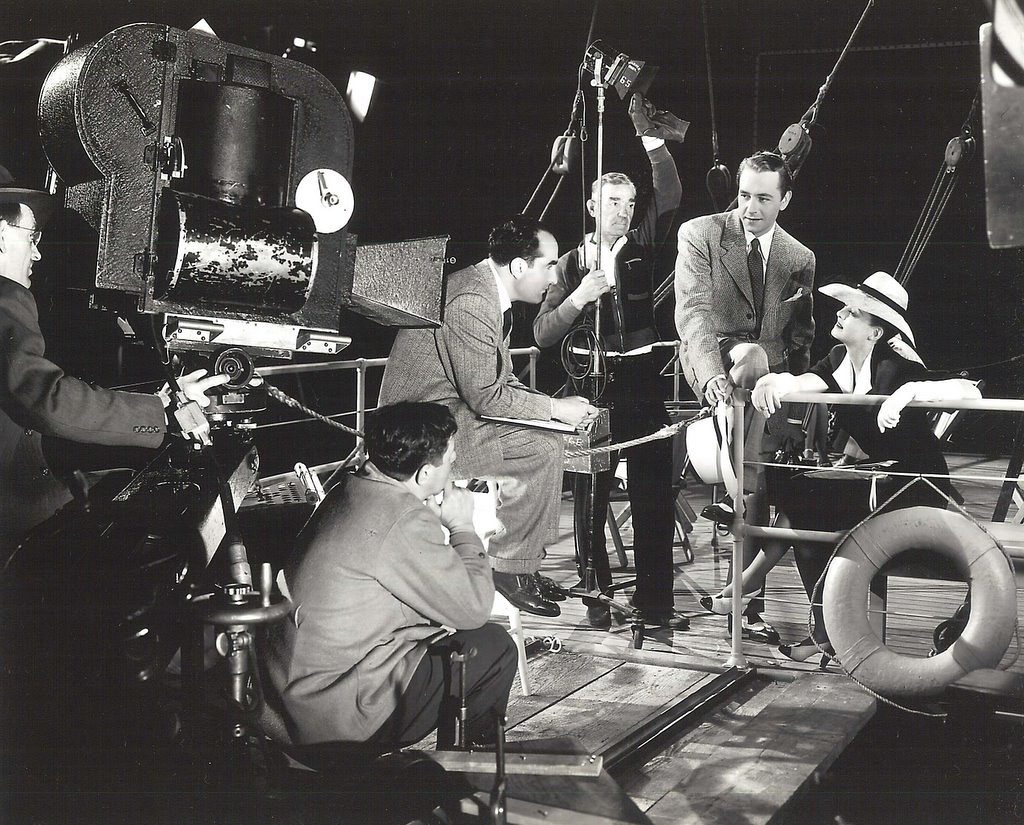

Warners’ version of The Petrified Forest was designed in part to showcase Bette Davis in an altogether quieter register than previously seen in RKO’s Of Human Bondage (1934), when Warners had loaned Davis out to support Leslie Howard in a movie based on Somerset Maugham’s autobiographical novel of 1915.

Davis joined the cast of The Petrified Forest in October 1935, shortly after completing work on Dangerous. While this gave her little time to recuperate, it did offer her a change of pace and the chance to reveal the quieter side of her persona. In order to perform the role played by Peggy Conklin at the Broadhurst Theatre, Davis subdued her histrionic skills and utilised a much more low-key register than audiences and critics had become accustomed to over the last year. [Chapter 7, page 176]

One of the challenges facing Davis when playing the role of Gabby Maple was that she needed to attract sufficient audience interest and sympathy so that her character would register as important to the main plot (the doomed love story) and be meaningful, while simultaneously blending into the background, enabling Howard to take his rightful place as the star of this drama. Howard’s lack of histrionics, energy and animation made this difficult. Resisting the urge to steal the scene when performing opposite him cannot have been easy. However, in doing so, Davis proved her professionalism. [Chapter 7, page 176]

Another challenge for Davis when joining the cast of The Petrified Forest in October 1935 was that she would be sharing the spotlight with two talented actors who had honed their performances in this drama over six months on the Broadway stage, performing their roles on no fewer than 197 occasions between January and June 1935. In contrast to Howard and Bogart, Davis had very little time between the end of filming on Dangerous and the start of The Petrified Forest in which to develop her characterisation, and devise and refine her performance. [Chapter 7, page 177]

After its premiere at the Radio City Music Hall on February 6, 1936, The Petrified Forest received a considerable amount of praise from the New York critics for its aesthetic qualities, the credibility of the story and the actors’ performances. It was widely praised for its adult themes, intelligently written script and Archie Mayo’s artful direction. [Chapter 7, page 180]

Repeatedly heralded as a distinguished Hollywood production that remained faithful to (and even improved upon) the original Broadway production, The Petrified Forest was also seen as a showcase for fine acting. [Chapter 7, page 181]

The release of The Petrified Forest in February 1936 was an achievement for Warner Bros. and a landmark in the careers of Howard, Bogart and Davis. For Howard, it marked the peak of his popularity and power on Broadway and in Hollywood, starring in a prestige picture at Warners based on his own co-produced star vehicle that had been written for and in consultation with him by one of America’s leading contemporary playwrights.

For Bogart, it reversed his declining career as an actor, on the back of which he won rave reviews, a new image, new fans and a long-term contract at Warner Bros. [Chapter 7, page 181]

For Bette davis, it was another opportunity to act again with Leslie Howard after her spectacular appearance with him in Of Human Bondage. More importantly, it gave her the chance to demonstrate the subtlety of her acting style after a series of more histrionic roles. While developing and showcasing her abilities to underplay as well as perform charming, naive and innocent characters, The Petrified Forest proved that Davis was eminently well suited to starring in prestige pictures based on acclaimed stage plays. [Chapter 7, page 181]

Chapter 7 can be downloaded from here: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-40658-3_7

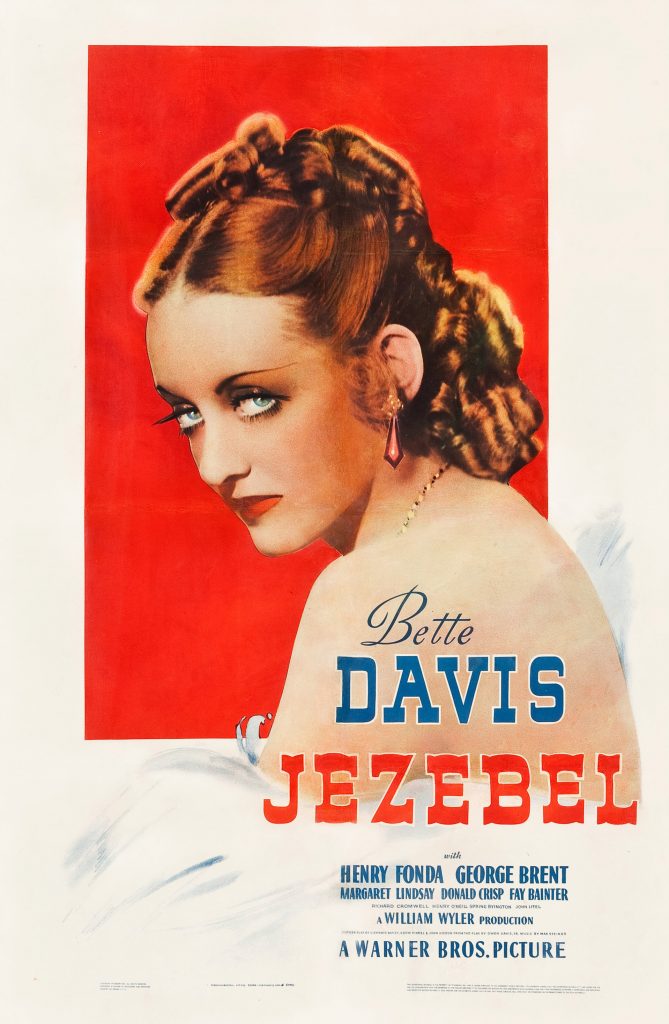

When Warners increased production of prestige pictures in the mid- to late 1930s, it transformed a hard-working contract player into one of Hollywood’s most critically acclaimed and commercially successful actors. Bette Davis’ starring roles in Jezebel (Wyler 1938), Dark Victory (Goulding 1939), The Old Maid (Goulding 1939) and The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (Curtiz 1939) brought her and her studio considerable acclaim from New York critics, as well as recognition from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, in addition to earning substantial profits. By casting Davis in big-budget emotional dramas based on stage plays, Warners hit upon a winning formula for success, while consolidating its reputation as a premier producer of quality drama. [Chapter 8, page 189]

[In Jezebel] Davis had never looked more beautiful on film. More importantly, her acting had never seemed so confident, controlled and finely executed than when playing this feisty, rebellious, wilful and independent young heiress, whose transgressions cause her to be socially ostracised, after which she loses the man she loves to another woman. [Chapter 8, pages 195-196]

Based on a stage play of the same name by Owen Davis, which had a short run at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre in December 1933 and January 1934, Jezebel was tailored to present Davis to best advantage. [Chapter 8, page 196]

The screenplay by Clement Ripley and Abem Finkel, with additional material by John Huston, was carefully crafted to accommodate her personality and public persona at this time. Consequently, Davis’ distinctive star image crystallised in Jezebel by giving the actor a character she could fully embody. Working with such a script made it easier for Davis to identify with her role, create her characterisation and craft her performance. [Chapter 8, page 196]

Yet another contributing factor to her credible characterisation was the work of the dialogue director Irving Rapper. With Rapper’s assistance, Davis analysed, rehearsed and worked out the significance of her lines, identifying key words and phrases, while experimenting with different ways of delivering them prior to being called to the set. Meanwhile, Carleton S. Reymond, a professor at Louisiana State University, helped Davis to perfect her character’s Southern accent. Davis was nothing if not thorough when developing her characterisation of Julie Marsden. [Chapter 8, page 196]

Davis’ main preoccupation at this stage in her career was to build credible and complex characters that audiences could understand, believe in and identify with. Herein lay her ability to move audiences, generating a strong emotional response. Warners certainly capitalised on this ability when casting Davis in a series of heavyweight emotional dramas (or melodramas) in 1939 – Dark Victory, Juarez, The Old Maid and The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex – all based on stage plays produced on Broadway between 1926 and 1935. [Chapter 8, page 197]

Of all the films Davis made in 1939, Dark Victory stands out as one of her finest acting achievements. Adapted specifically for her by Casey Robinson from Brewer and Bloch’s stage play, the screenplay incorporated aspects of the star’s strong, independent and feisty persona, while capitalising on her established screen chemistry with actors such as Humphrey Bogart and George Brent. It was also helped by her productive working relationship with director Edmund Goulding and cinematographer Ernest Haller. Meanwhile, Irving Rapper worked closely with Davis on analysing her script and trying out different ways of delivering her lines. Finally, Max Steiner’s music was used to heighten the emotionality of Davis’ performance, underscoring her gestures, expressions and movements in order to produce a powerful and moving romantic drama. [Chapter 8, page 197]

Eloquence, tenderness and heartbreaking sincerity were … the keynotes of Davis’ performance in The Old Maid, which was once again directed by Edmund Goulding, with a script by Casey Robinson. This not only proved to be Davis’ highest-grossing film of 1939 but it also earned her considerable adulation from the New York film critics. [Chapter 8, page 198]

The Old Maid earned Davis some of the best reviews of her career and marked a high point in terms of the critical reception of her acting. [Chapter 8, page 199]

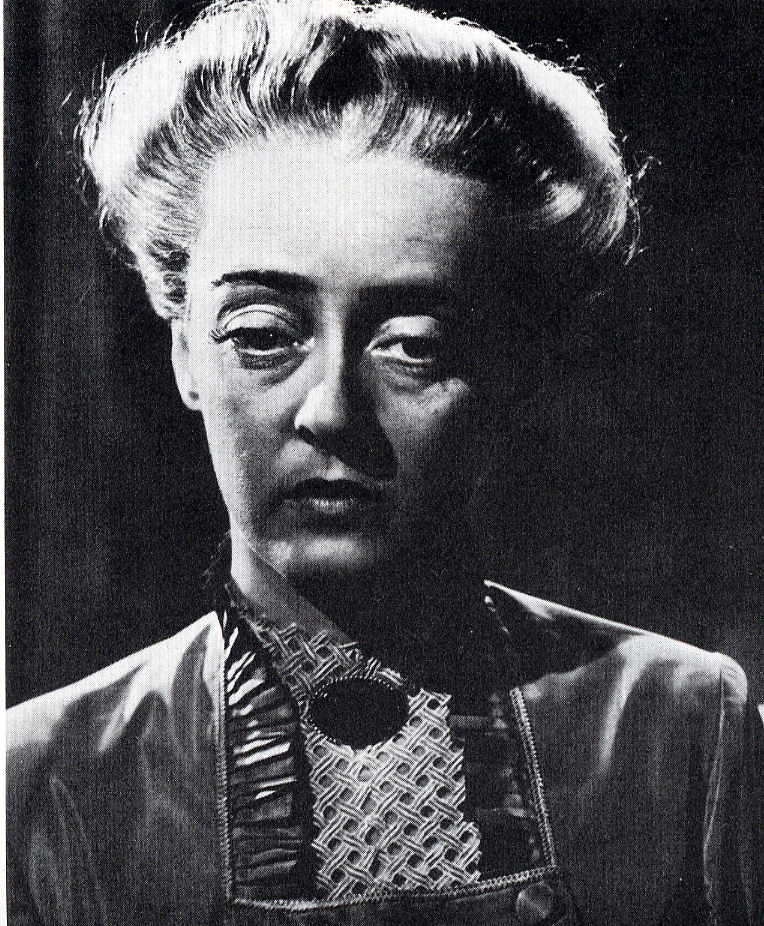

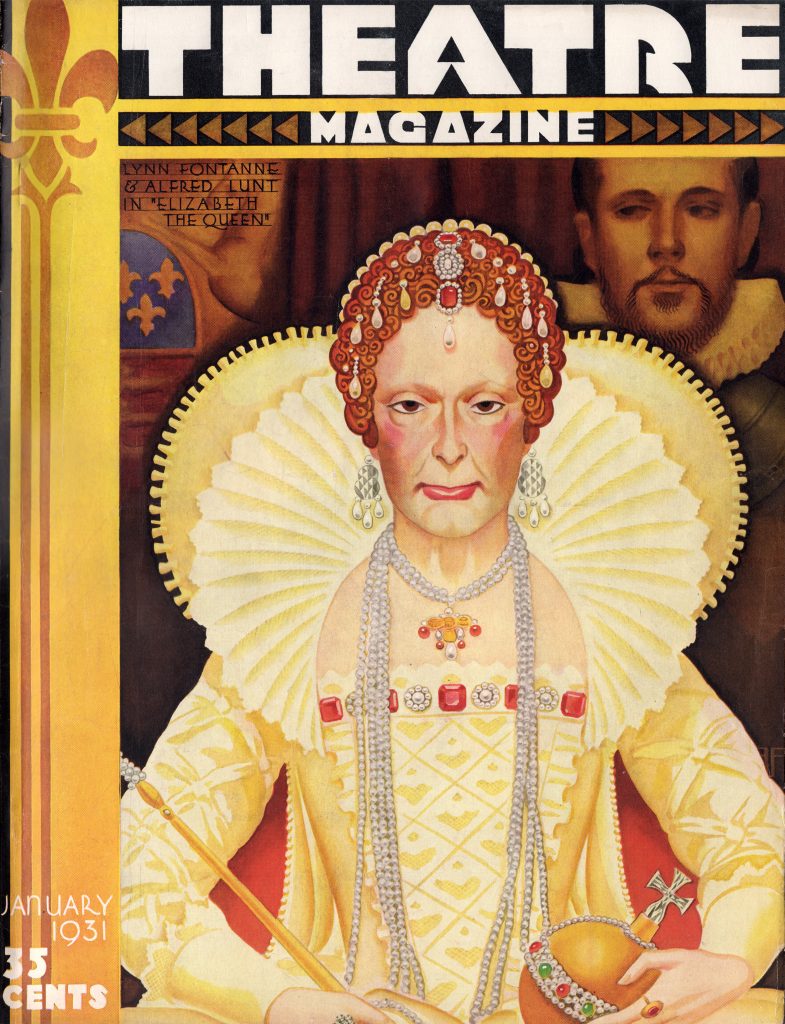

Davis enjoyed a magnificent run of critically acclaimed performances in her warner films of 1939, although this was almost jeopardised towards the end of the year when she was cast in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex alongside the Australian actor Errol Flynn. [Chapter 8, page 199]

This was based loosely on Maxwell Anderson’s verse play Elizabeth, the Queen, which had been staged on Broadway by the Theatre Guild in 1930, with the English actress Lynn Fontanne performing the title role. [Chapter 8, page 199]

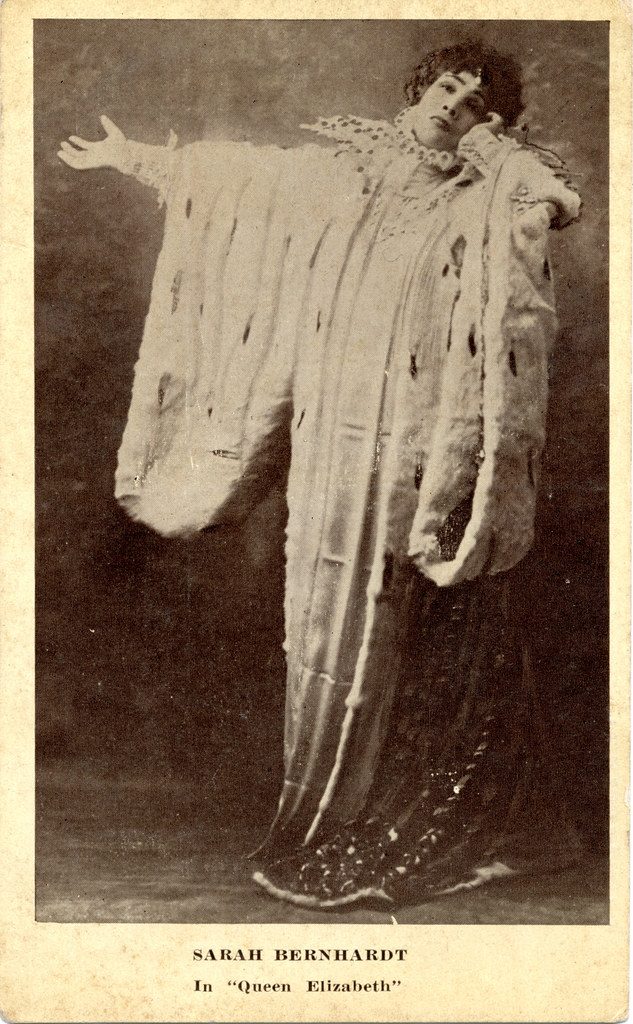

The film presented Davis with one of the greatest challenges of her career. Not only did the 31-year old American actress have to convincingly play an English woman in her early sixties but she also had to follow in the footsteps of some highly acclaimed actresses who had made the part of Queen Elizabeth their own. [Chapter 8, pages 199-200]

Audiences and critics were just as likely to compare Davis’ performance with that of the English actress Flora Robson, who had starred as Queen Elizabeth I in the British film Fire Over England (Howard 1937) just 2 years earlier. [Chapter 8, page 200]

American film critics had raved about Robson’s magnificent performance, in which she maintained a perfectly still body to signify the queen’s high social status. Robson made a point of using only minor movements in order to convey her character’s emotional repression, as the queen is shown repeatedly putting duty before passion. Even in the most intimate scenes, Robson portrayed Elizabeth as a woman in command of her feelings. [Chapter 8, page 200]

Davis, on the other hand, decided to portray the queen as being continually at odds with her own emotions and in a perpetual state of confusion and ambivalence bordering on hysteria, however strong and commanding she might appear in public. In so doing, she was able to distinguish her portrait from that of Robson, making strenuous efforts to make Elizabeth her own in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex. [Chapter 8, page 200]

Davis based her characterisation of Elizabeth mostly on the screenplay, which describes the queen as deeply conscious of her age, as sleepless and tortured, anxious that she might be going mad. She is not only jealous and wary of the attractive and adored Robert Devereaux, Earl of Essex (Errol Flynn) but is also convinced that her courtiers are plotting against her, thereby placing her in a vulnerable position in which she can trust no one. To convey Elizabeth’s neurosis and paranoia, as well as her advanced age, Davis consistently used a full-bodied shake that extends down her back, across her shoulders, her arms and into her hands. In many scenes, her fingers fly about (apparently uncontrollably), waving and patting things (apparently compulsively). This produced a highly charged and exhausting performance of Elizabeth in which the queen’s body appears to be consumed by hysterical symptoms. [Chapter 8, pages 200-201]

Errol Flynn’s approach to screen acting was markedly different to that of Bette Davis. Flynn was not generally considered to be an accomplished actor and his attitude towards his work was anything but conscientious. Frequently, he arrived on set ill-prepared, having failed to learn his lines and given no thought as to how he might deliver them. Consequently, shooting was often interrupted when Flynn repeatedly fluffed his lines, to the exasperation of his co-star. By 1939, however, he had grown complacent and learned to compensate for his deficiencies as an actor with charm, graceful and athletic actions, and by relying on his confidence and beauty. [Chapter 8, page 202]

To the modern eye and ear, Davis’ performance in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex may well seem problematic, as well as less credible, heartfelt and accomplished than in Dark Victory and The Old Maid, where she used greater levels of restraint. To modern eyes and ears, Davis may well seem hammy and eccentric rather than nuanced and natural as Elizabeth. [Chapter 8, 204]

[However,] For the influential New York film critics in 1939, Bette Davis was undisputedly one of Hollywood’s greatest screen actors. Rather than compare her to the likes of Greta Garbo, Greer Garson, Ingrid Bergman or Vivien Leigh, they generally compared her to the queens of the American stage, notably Lynn Fontanne, Katharine Cornell, Tallulah Bankhead and Helen Hayes. In 1939, these acclaimed Broadway stars were concentrating on theatre work. And for as long as they continued to work exclusively in the theatre, Bette Davis was able to thrive in Hollywood with little serious competition in terms of dramatic acting, enabling her to create her own distinctive versions of roles made famous on Broadway.

Chapter 8 can be accessed and downloaded here: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-40658-3_8

Broadway made a deep impression on Warner Bros. at a formative stage of its history. The drive to bring stage plays to the big screen and export them around the word lay behind the company’s creation of Vitaphone in New York, Warner staff being tasked with hiring Broadway talent, securing screen rights to plays and adapting them into motion pictures that could do what Broadway had been doing for over two hundred years, namely talk and sing. [Chapter 9, pages 217-218]

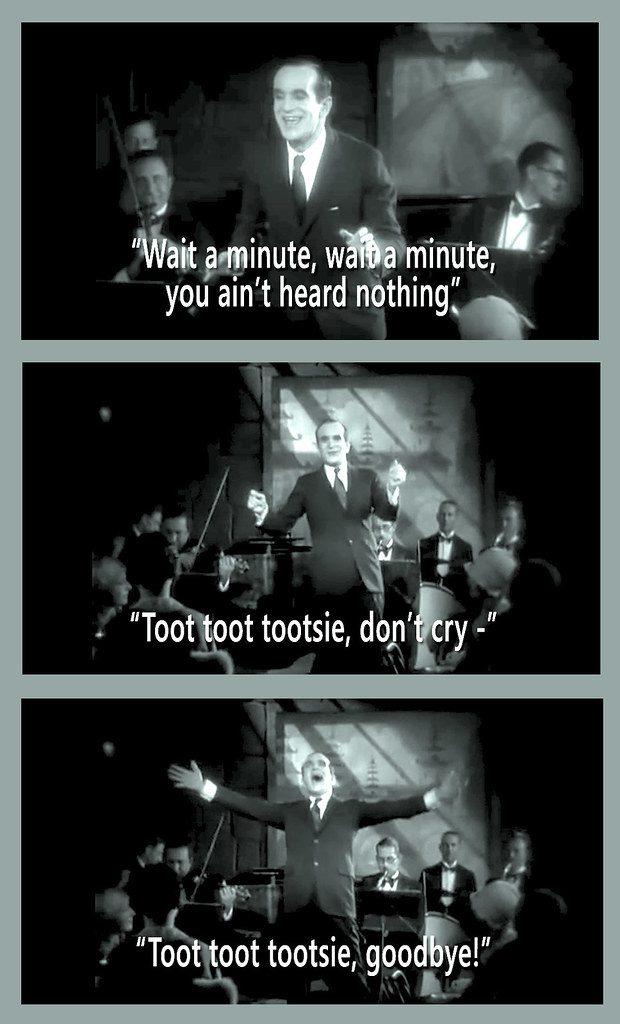

Now Broadway stars and plays sprang to life on the screen in a way they had never done before, with snap and verve, making their silent predecessors seem slow and stilted in comparison. Al Jolson’s abundant energy burst through in the sound sections of The Jazz Singer and electrified audiences, leaving them with an urgent desire to see and hear more movies that could talk and sing. [Chapter 9, page 218]

Consequently, even greater numbers of moviegoers flocked to see him in his all-talking picture The Singing Fool (Bacon 1928), one of many films in the late 1920s that swelled the coffers at Warner Bros. to such an extent that it could transform itself into one of the world’s leading producers of motion pictures by buying up its competition and outbidding its rivals for the best people and plays on the New York stage at the very moment that Broadway was in crisis. [Chapter 9, page 218]

By 1939, many of Warners’ biggest Broadway stars had come and gone, including John Barrymore, Al Jolson, George Arliss, Ruth Chatterton and Leslie Howard. While Howard was filming Gone with the Wind at MGM, George Arliss and Ruth Chatterton had both retired from filmmaking by this time. Barrymore, meanwhile, was back at Paramount and Jolson was at Twentieth Century-Fox working for the former Warner producer Darryl F. Zanuck. This exodus paved the way for Bette Davis to become Warners’ biggest star in 1939, particularly after she won an Oscar for her performance in Jezebel (1938) and when her critically acclaimed star vehicle The Old Maid (1939) earned more than $2 million at the box office. [Chapter 9, page 218]

Bette Davis’ approach to crafting meticulously worked out characterisations based on detailed script analysis, research and a cool-headed approach to performance did not preclude her from using a histrionic acting style featuring many of the “mannerisms” that were originally inspired by Arliss, such as clenching and unclenching her hands to express tension and agitation. [Chapter 9, page 220]

Bette Davis often used an assortment of elaborate and emphatic looks, facial expressions, movements and gestures as part of her on-screen performances. These not only gained her a significant degree of audience and critical attention but also helped her to convey the inner life of her characters. This was particularly true of those undergoing some kind of psychological crisis triggered by an extraordinary set of circumstances. Consequently, histrionic acting was as much a feature of Davis’ The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex in 1939 as it was in Arliss’ Disraeli 10 years earlier. This demonstrates the durability and continuing appeal of screen performances that at key moments could be perceived as virtuosic. [Chapter 9, page 220]

The days when actors provoked audiences to burst into rapturous applause and demand encores of their favourite moments might have passed long ago; nevertheless, some vestige of that tradition appears to have survived in the screen performances of Barrymore, Arliss and Davis. This meant that these actors straddled the precariously thin line between great and ham acting, which inevitably made their performances both thrilling and unpredictable. [Chapter 9, page 221]

Arliss’ Oscar for his performance in Disraeli (1929) and Davis’s Oscar for Jezebel (1938) suggest that the jury of the Motion Picture Academy endorsed ostensive acting from star performances that included pictorial and histrionic effects. Similarly, the critical adulation for Davis’s performance in The Old Maid in 1939 suggests that the influential New York film critics appreciated naturalistic acting with a dash of something extra to spice it up. Praise for virtuosic performances, even theatricality, can be found in many of the reviews that featured in the columns of the New York papers throughout the 1920s and 1930s. [Chapter 9, page 221]

When Barrymore, Arliss and Davis produced elaborate gestures and facial expressions that harked back to an earlier style of performance, they put their reputations as distinguished screen actors on the line. So why did they take such a risk? There are numerous possible answers, including a lapse of concentration, a momentary misjudgment about the scale and impact of their actions, the desire to outshine (or overshadow) a fellow cast member by stealing the limelight at a critical moment in the drama. However, there may well be another reason. Overly gestural and expressive moments might well have occurred due to an actor’s recognition that audiences and critics appreciated having a palpable sense of a performance being produced. There certainly seem to be moments in each of these highly accomplished actors’ films when they render visible what at other times they are at pains to make imperceptible. If this is the case, then such highly professional and consummate artists as Barrymore, Arliss and Davis permitted themselves the occasional liberty of thrilling an audience with an action that threatened to undermine the reality effect being so carefully constructed elsewhere. [Chapter 9, pages 221-222]

Analysis of the screen performances of some of the most celebrated film actors of the 1920s and 1930s challenges the idea that pictorial and histrionic acting disappeared from American cinema in the 1910s. If this is accurate, it constitutes a significant revision of the history of acting in Hollywood. Further revisions might be gained by attending to the work of screenwriters, stage managers, unit producers, producers (aka supervisors) and dialogue directors at Warner Bros. and elsewhere, particularly in terms of their collaborations with actors and stars. [Chapter 9, pages 222-223]

There is still much to uncover about Hollywood’s long-standing, extensive and intricate connections with Broadway. The full history of this relationship between two dominant and influential entertainment industries remains to be written. As part of that ongoing historical project, Warners’ evolution as a studio needs to be revisited and retold in different ways, investigated by different means to address a different set of issues and, in so doing, bring further new facts to light. [Chapter 9, page 225]

Chapter 9 can be accessed and downloaded here: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-40658-3_9

Copies of When Warners Brought Broadway to Hollywood, 1923-1939, including an eBook, can be purchased from here: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/978-1-137-40658-3

An in-depth review of the book can be found here: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/732502/pdf

Be the first to write a comment.