I love melodrama. I love the way that it takes the everyday and transforms in into something magical, memorable and meaningful. I love the way that music dominates from the start and sweeps you up, carrying you along, lifting your heart up only to bring you suddenly crashing back down to earth, making you feel the protagonist’s joy and love, pain and anger, desperation and heartache in quick succession. It’s bold and lush, unashamedly and unapologetically romantic.

I love the fact that the characters of melodrama are flawed and if they are in any way heroic it’s in small and often unrecognised ways that usually go unrewarded. I love the fraught and tangled ways in which these films try to distinguish between good and bad behaviour, between notions of right and wrong, often finding it almost impossible to draw clear distinctions between what are so often supposed to be opposites.

I love the amazing coincidences that bring together two people who have been desperately trying to avoid each other or the sudden combination of extraordinary events that push a character to the very limits of endurance or patience so that the cracks in their makeup appear, threatening to tear them apart.

I love the (almost) happy endings that grant these flawed and struggling souls some degree of fulfilment even if it’s far removed from everything that they’d once been hoping for. I love seeing how characters emerge stronger or at least with a better understanding of themselves after all the things they’ve been put through for my entertainment and understanding. I love the chance to revel in their pleasures and pains, laughing and crying (sometimes at the same time) as the narrative hurtles along on an emotional rollercoaster ride that keeps me gripped and hanging on to every word, every look and every sigh. Yes, I really do love melodrama!

So when my former PhD student John Mercer asked me to collaborate with him on writing a small (but perfectly formed) book on film melodrama, I couldn’t resist. Despite its size, this Wallflower Press Short Cuts guide to melodrama was actually quite a challenge to write given the amount of academic work that we needed to cover and the complexity of the debates on melodrama that had taken place within Anglo-American film studies since the early 1970s. For me though, this was a great way in the early 2000s to reconnect with some of the research that had made a profound impression upon me as a film student back in the mid-1980s, making me want to pursue film studies at post-graduate level. In fact, it was Thomas Elsaesser’s seminal essay ‘Tales of Sound and Fury: Observations on the Family Melodrama’ that not only inspired me to write my undergraduate thesis on ‘The Ideology of the Hollywood Family Melodrama’ (1987) but also to go to study for a masters degree in film with the esteemed professor at the University of East Anglia in 1988. It was also Thomas who supervised my masters thesis on All About Eve (1950) and persuaded me to develop this into a PhD on Bette Davis and her star vehicles from 1938 to 1950.

Thomas’s ‘Tales of Sound and Fury’ (1972) had been my introduction to studying melodrama as an undergraduate student along with Christine Gledhill’s entry on the topic in Pam Cook’s The Cinema Book (1984). Christine’s essay ‘The Melodramatic Field’ at the start of her seminal anthology Home is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film (1987) subsequently forced me to rethink everything I thought I knew about melodrama and take a much more open-minded and historical approach to my own investigations. Studies by Steve Neale, Rick Altman, Barbara Klinger and Linda Williams, among others, consistently challenged my notions of melodrama and kept me hooked on researching further into this increasingly wide-ranging and heavily contested area of film studies throughout the 1990s.

Writing Chapter One of Melodrama: Genre, Style, Sensibility, enabled me to revisit and remap this scholarly journey at the start of the twenty-first century. I quickly discovered that my initial enthusiasm for what I think of as a mode of cinema rather than a genre hadn’t diminished over time, however much the debates about it within film studies had changed and been consistently revised. Charting those revisions proved to be a useful way from me to retrace my steps from student to lecturer.

When it came to writing our short guide to melodrama, John and I agreed upon a division of labour. I undertook Chapter One on Genre and the first half of Chapter 3 on Sensibility, as well as the Conclusion. Meanwhile, John produced the Introduction, Chapter 2 on Style and the second half of Chapter 3. This worked well, our personal contributions fitting together fairly seamlessly and our own particular interests and expertise complementing one another’s to create something more wide-ranging than either of us could have done single-handedly. For me, this was a really productive and rewarding collaboration, particularly as the book subsequently found its way onto the reading lists of college and university courses in so many countries around the world, including India and Japan.

Blurb on the back cover:

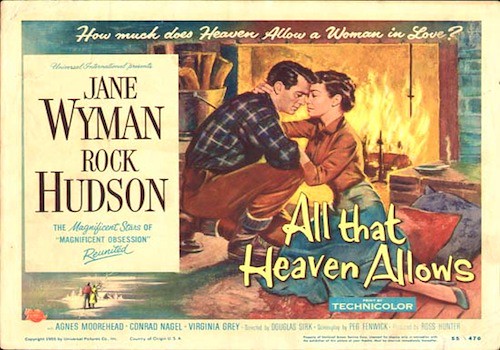

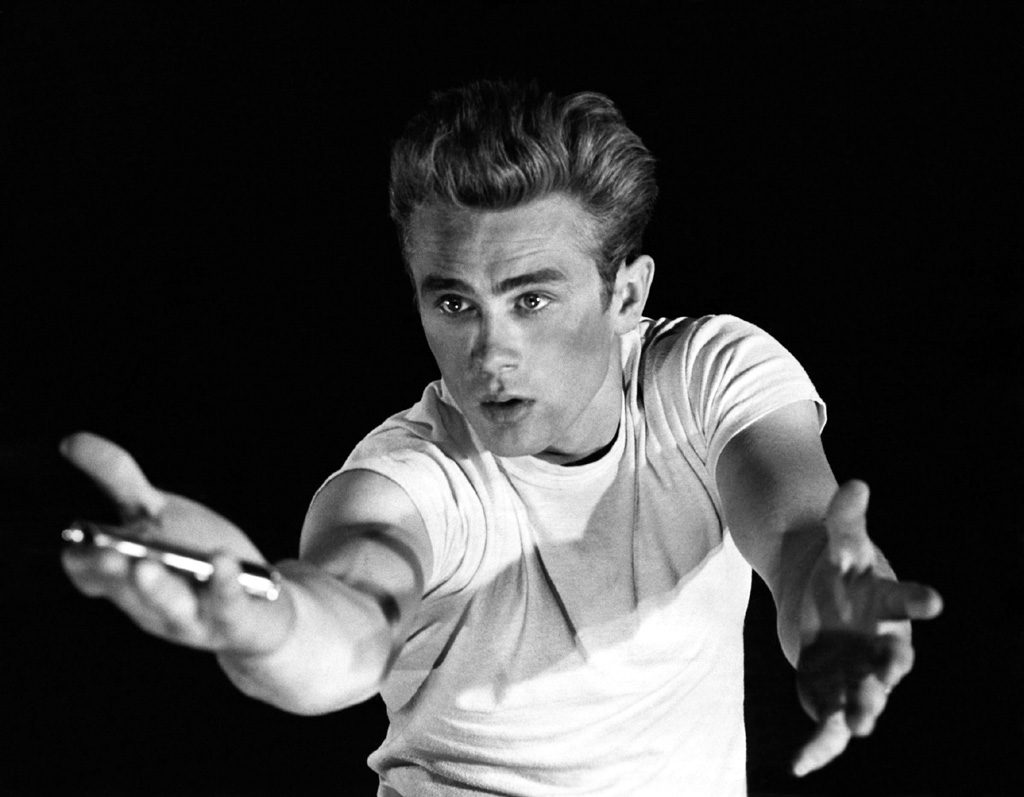

Melodrama: Genre, Style, Sensibility is designed as an accessible overview of one of the most popular genres at undergraduate Film Studies. The book identifies three distinct but connected concepts through which it is possible to make sense of melodrama; either as a genre, originating in European theatre of the 18th and 19th century, as a specific cinematic style, epitomised by the work of Douglas Sirk or as a sensibility that emerges in the context of specific texts, speaking to and reflecting the desires, concerns and anxieties of audiences. Films discussed include All That Heaven Allows, Safe, Fear Eats the Soul, Black Narcissus, Suddenly Last Summer and Rebel Without a Cause. Each chapter includes overviews of key essays, analyses of significant and widely studied films and includes an annotated reading list.

Some extracts:

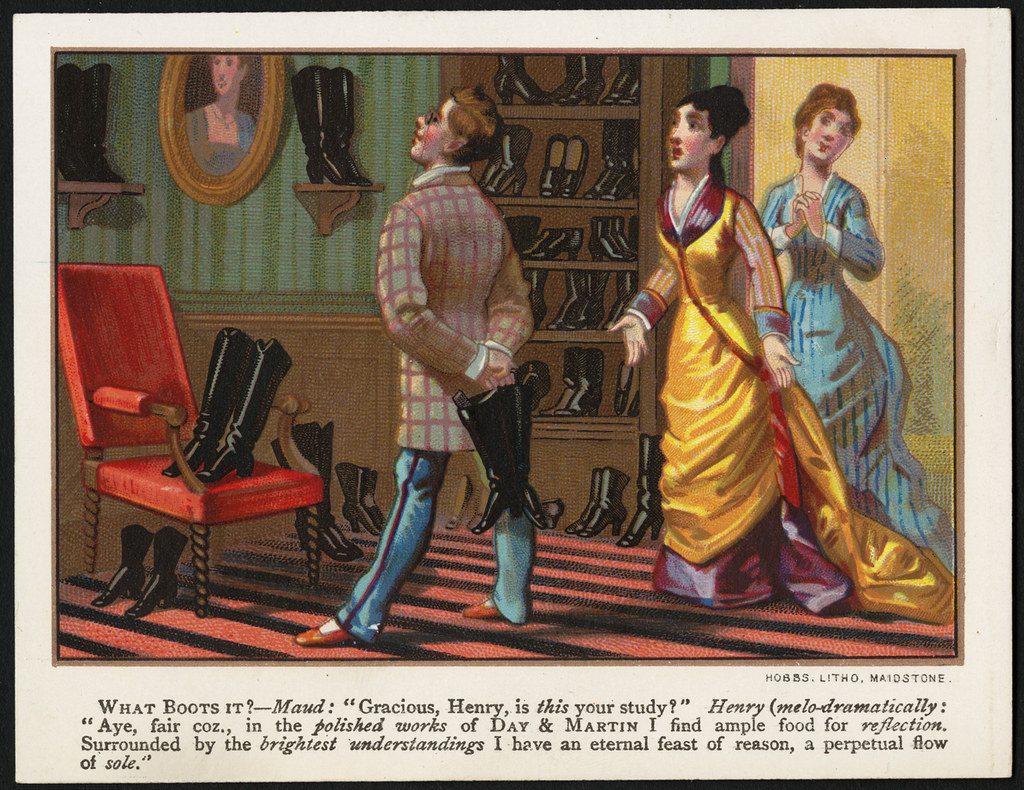

As Gledhill and others have explained, melodrama emerged onto the stage as a new theatrical genre combining elements of both comedy and tragedy. At the level of pure entertainment, melodrama established notoriety through its astonishing twists and turns of fate, suspense, disaster and tragedy, its last-minute rescues and its happy endings. Whilst many of its themes were derived from morality plays, folk-tales and songs, stylistically it drew upon the conventions of pantomime and vaudeville. A key feature was its dependence upon an established system of non-verbal signs, gestures, mise-en-scene (sets, props, costumes and lighting) and music. The themes and styles of this highly popular theatrical form proved eminently suitable for adaption to the new cinematic medium, providing an obvious appeal for filmmakers seeking the widest and largest possible audience for their new product. [page 7]

In much the same way that film scholars had defined and demarcated the genre of the ‘western’, film theorists and historians identified the constituent features of the Hollywood family melodrama, providing a credible form of generic categorisation that enabled melodrama to be studied as a genre. The pioneering work of Thomas Elsaesser (1972) played a key role in this respect. He is commonly held to have been the first film critic to use the term ‘family melodrama’ and also to take it, implicitly at least, as the ultimate form of film melodrama. Certainly, many film scholars subsequently assumed that his comments regarding the Hollywood family melodrama were applicable to Hollywood melodrama more generally. [page 8]

Elsaesser’s article, ‘Tales of Sound and Fury’ (1972), was the first notable study of melodrama, representing many of the concerns and preoccupations of critical thinking of the 1970s. In this article, Elsaesser suggested that, under certain social and production conditions, melodrama could be seen as ideologically subversive. For Elsaesser, the family is not just an important political institution in itself but is also a means through which social crises can be delineated in personalised and emotional terms. He noted the emergence in the 1950s of the impotent hero, trapped within a domestic interior and confined by codes of behaviour appropriate to the family. This he took as an indication of the shift in the ideological conditions pertaining under post-war advanced capitalism. Moreover, for Elsaesser, this represented a shift to a critique of individualism, in which the bourgeois family became the site of both social and emotional isolation and, consequently, of the failure of the drive to self-fulfilment. [page 21]

Melodrama owes its longevity to the fact that it has existed – and continues to exist – as a category of films defined differently at different times by different types of people (both within and beyond the film industry). Different kinds of film can be (have been and will continue to be) grouped together under this label not in any arbitrary fashion and not because anything can be thought of as melodrama but rather because it is an evolving form. It evolves with every new film that is made that refers directly to its established canon: such as Far From Heaven (Todd Haynes, 2002). [page 37]

It evolves with every advertisement that describes a film (old or new) as a melodrama or as melodramatic. It evolves when groups of film scholars discuss the meaning of the term and when a film historian discovers a print of an unknown film that can be said to manifest stylistic or thematic features redolent of what has previously been described as melodrama. It also evolves when new media forms refer to, are promoted as, or are otherwise described as having some resemblance or affinity to what is commonly held to be some existing form of melodrama. For some, however, this may be too fluid, too slippery and too uncertain. For them, melodrama must either take one form or not be a genre at all. As melodrama has clearly never taken a single form and, over time, has developed many variants (that hardly seem to correspond at all in some cases), the alternative is to conceive of melodrama as something beyond genre … a style, a mode and even a sensibility. [page 37]

Melodrama consists of much more than the Hollywood family melodrama and the ‘woman’s film’. Since the 1980s, some film scholars have been rethinking melodrama beyond generic boundaries, as a style, mode, sensibility, aesthetic and rhetoric, crossing a range of genres, media, historian periods and cultures. During the mid-to-late 1980s, film scholars began to turn attention away from investigations into the ideology of the ‘family melodrama’ and the ‘woman’s film’ to find ways of understanding the distinctive narrational and aesthetic effects of melodrama across a diversity of genres, sub-genres and film cycles. High on the agenda was melodrama’s use of pathos and its emotional impact on audiences. So too was melodrama’s relationship to realism. Increasingly, film melodrama was linked to stage and literary melodrama, establishing it as part of a much wider tradition. At the same time, the term ‘melodrama’ was applied to an expanded (and expanding) canon of films. [page 78]

Home is Where the Heart Is. Here, in Gledhill’s introductory chapter, ‘The Melodramatic Field: An Investigation,’ a radically new conception of melodrama was set out and a new methodology for studying melodrama was proposed. Written just three years after she had outlined the form as a genre in her section on melodrama in The Cinema Book (Cook 1984), Gledhill now outlined the development of melodrama criticism in Film Studies and found it wanting. She noted the largely pejorative use of the term ‘melodrama’ by film scholars, which had prevailed in film criticism until Douglas Sirk’s 1950s films had been rehabilitated, regarded as ironic and subversive critiques of American ideology. Prior to this, she claimed, melodrama had been used by critics as the ‘anti-value for a critical field in which tragedy and realism became cornerstones of “high” cultural value’ (1987:5). [page 81]

The undertaking of such a potentially large academic project within the limited space of a chapter was (it would appear) to fill a perceived gap within Film Studies, undertaking the type of work which could have logically followed on from Elsaesser’s essay in 1972 had the ideological debate not imposed itself. Confined as it was to two sections of an introductory essay to the anthology of critical studies on melodrama and the woman’s film, Gledhill’s project here could never have been more than a sketch or a provisional investigation. Its purpose was to instigate a new approach and a new area of investigation for scholars of film melodrama rather than provide the definitive account. What it did do was identify an alternative body of scholarship on melodrama that film scholars might usefully consult in order to understand its historical development, cultural significance and aesthetic aspects. [page 84]

Gledhill’s position was almost entirely at odds with the other studies contained in her anthology (although sharing occasional sympathies). It was, in many ways, a call for the adoption of a completely new approach to melodrama within Film Studies rather than an endorsement of the approaches that had taken place already. Her position has subsequently been take-up most enthusiastically and most explicitly by Linda Williams. In her essay, ‘Melodrama Revised,’ she offered a ‘revised theory of a melodramatic mode – rather than the more familiar notion of the melodramatic genre’ (1998: 43). She argued that melodrama, rather than being a genre or any other sub-set of American filmmaking, is the pervasive American mode of filmmaking, constituting many genres and being ever-present. [pages 87-88]

We recognise, however, that the dramatic expansion of what is understood as melodrama (shifting from genre to more fluid forms such as style, mode, rhetoric, aesthetic, sensibility) makes this a potentially confusing area of film scholarship. Nevertheless, we also recognise that this has the potential to make melodrama more relevant as a critical tool, Students working in almost every aspect of film are likely to encounter the rhetoric of melodrama operating to greater or lesser extent. [page 115]

This could be in relation to a musical (Hollywood or Bollywood), a western (Hollywood or Spaghetti), in relation to a romantic comedy or a British heritage film. Some scholars and students of film will embrace this opportunity to rethink established generic categories and investigate the deeper structures of films that exist across virtually all genres. In such instances, the expanded notion of melodrama as a mode will be used to examine a more heterogeneous group of films in relation to each other. Others though may continue to cling on to a more established notion of melodrama as a genre or cluster of closely related genres and sub-genres. [ page 115]

Melodrama has always provoked strong emotions, not just from audiences but also from film scholars and critics. … No doubt melodrama will remain a contested area of Film Studies, providing an ever-expanding arena in which these battles can be fought out. As film students, we are all able to take up a position within this arena, to take sides or, alternatively, to attempt to arbitrate between the warring factions. Remembering that the tendency within melodrama is towards polarised conflict, if we embark upon this task as students of film, we should steel ourselves to face the sound and fury of our antagonists. Moreover, we should know from the outset that we are likely to fall victim to misunderstanding, even misrepresentation: that it could be a long time before the truth and value of our position is publicly recognised and that, in the meantime, many tears will have to be shed. [page 115]

See Christine Gledhill’s interview with me for the SCMS Fieldnotes project for more on the development of melodrama research in Film Studies since the mid-1970s. https://vimeo.com/473597082

Be the first to write a comment.